Duet

Duet

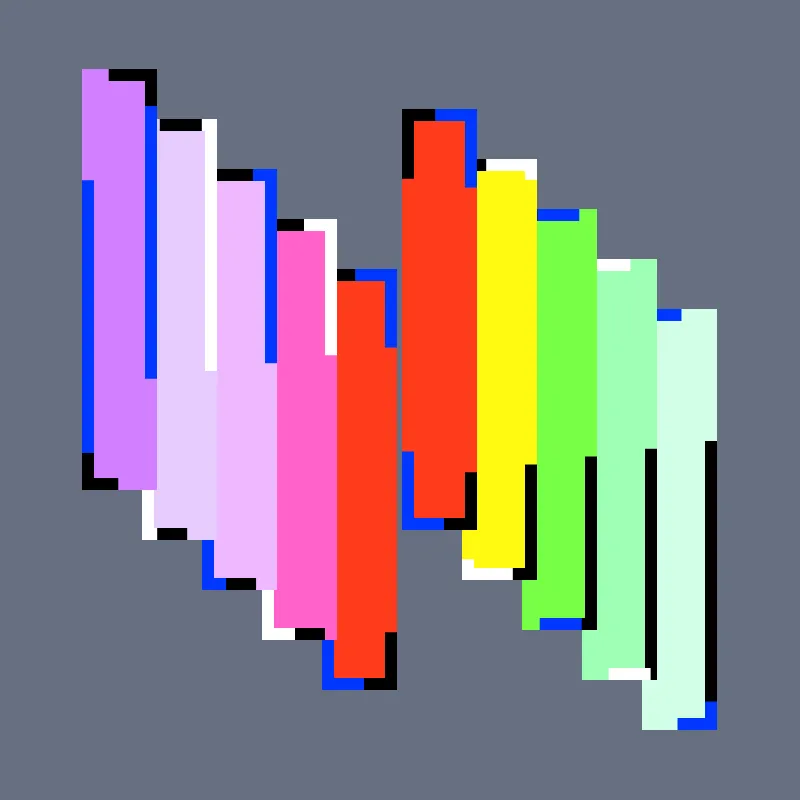

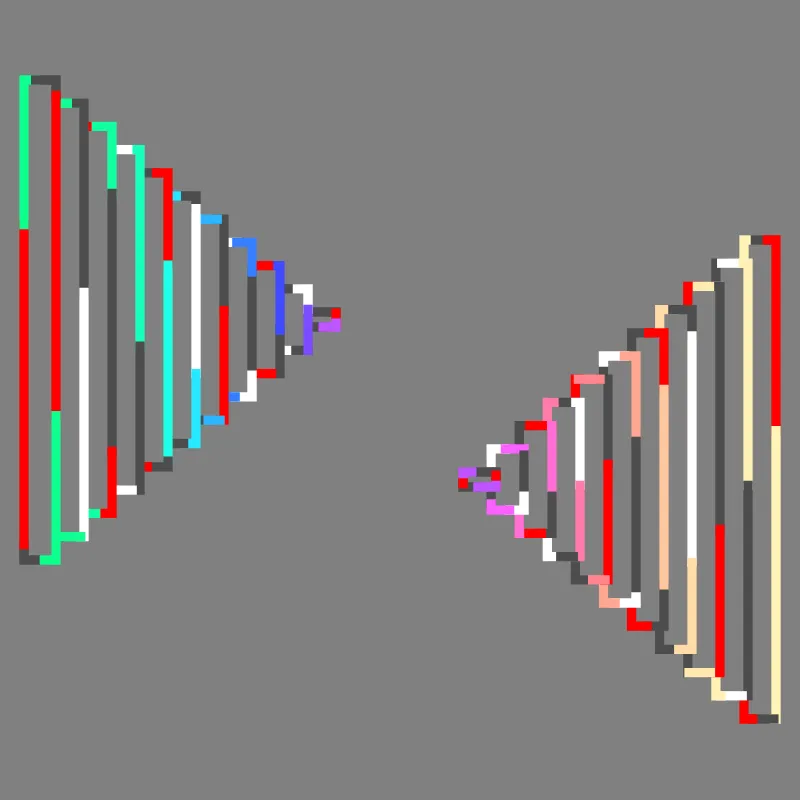

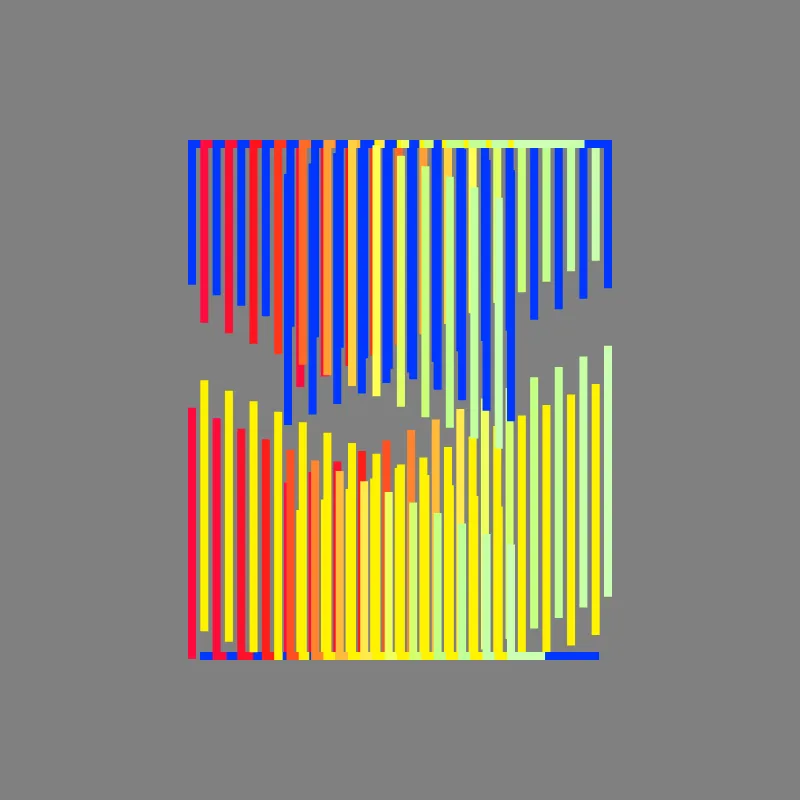

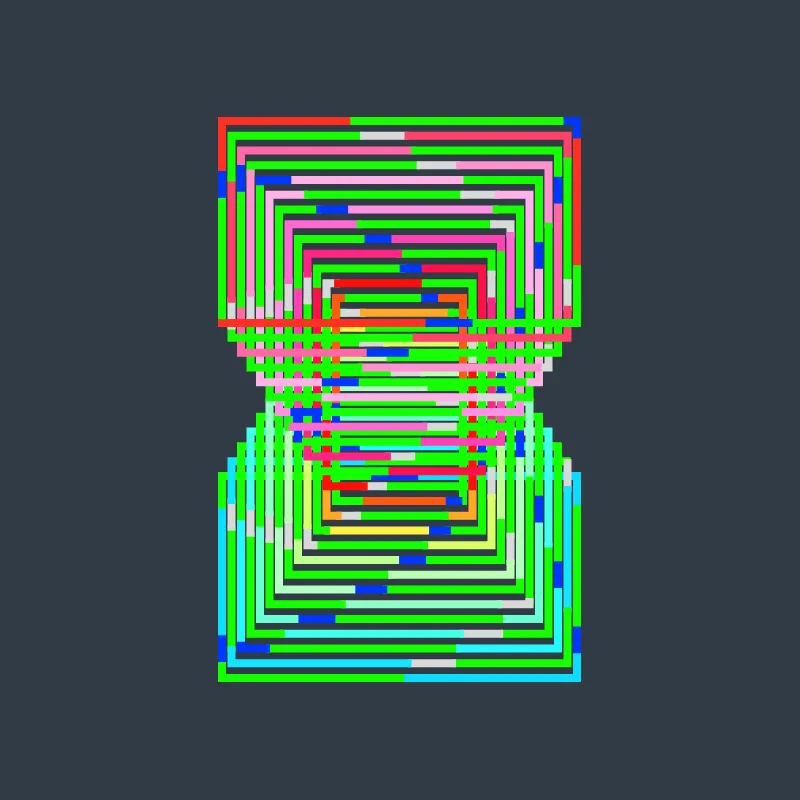

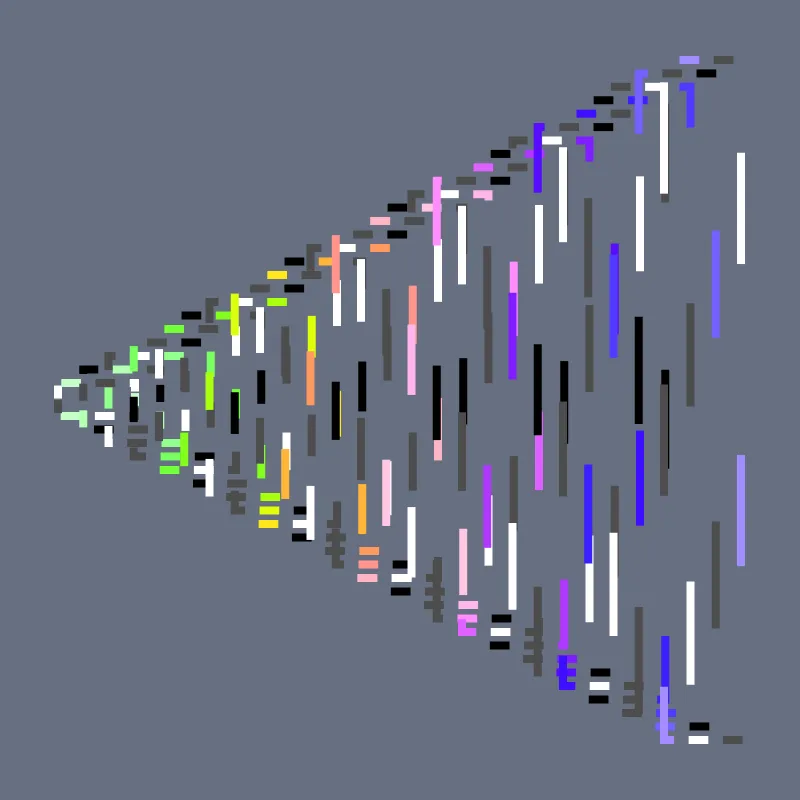

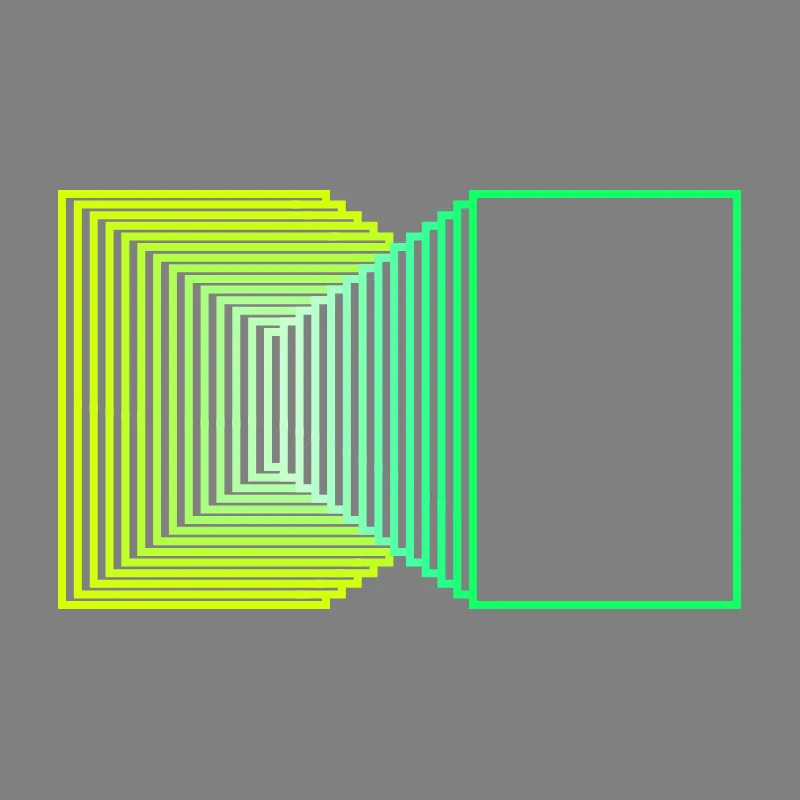

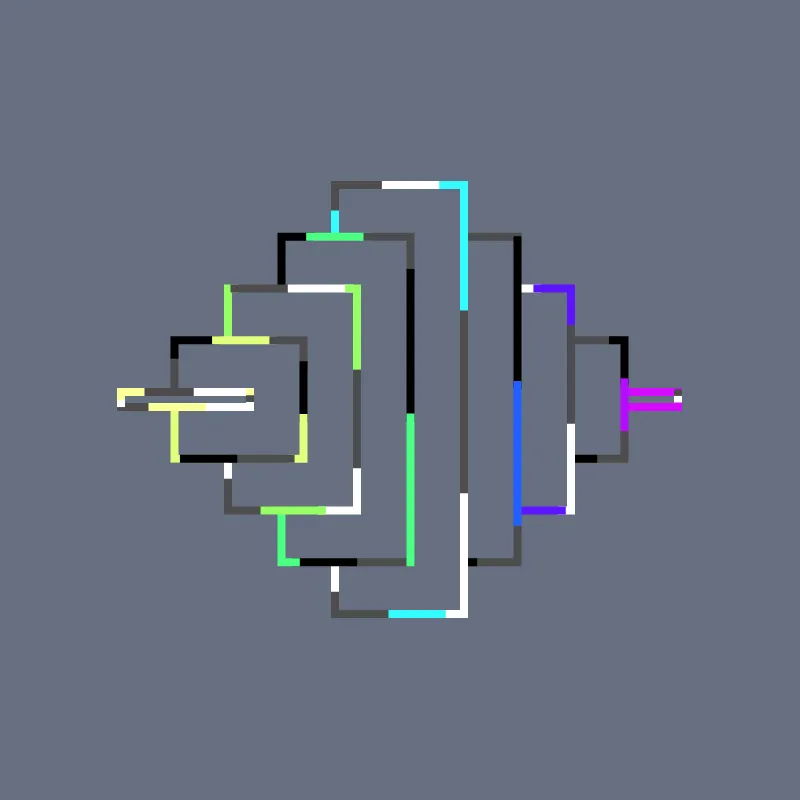

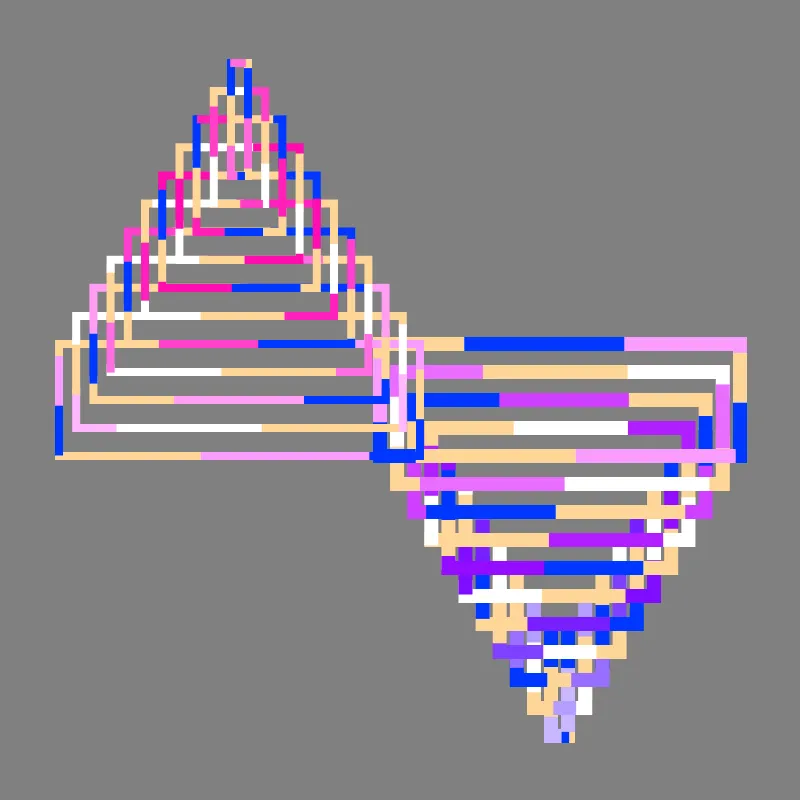

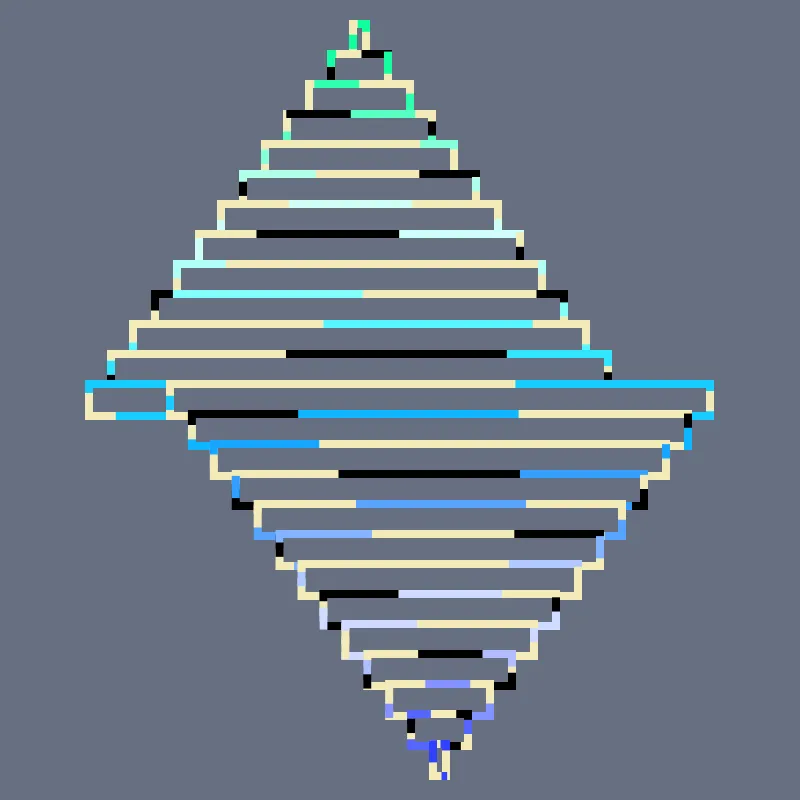

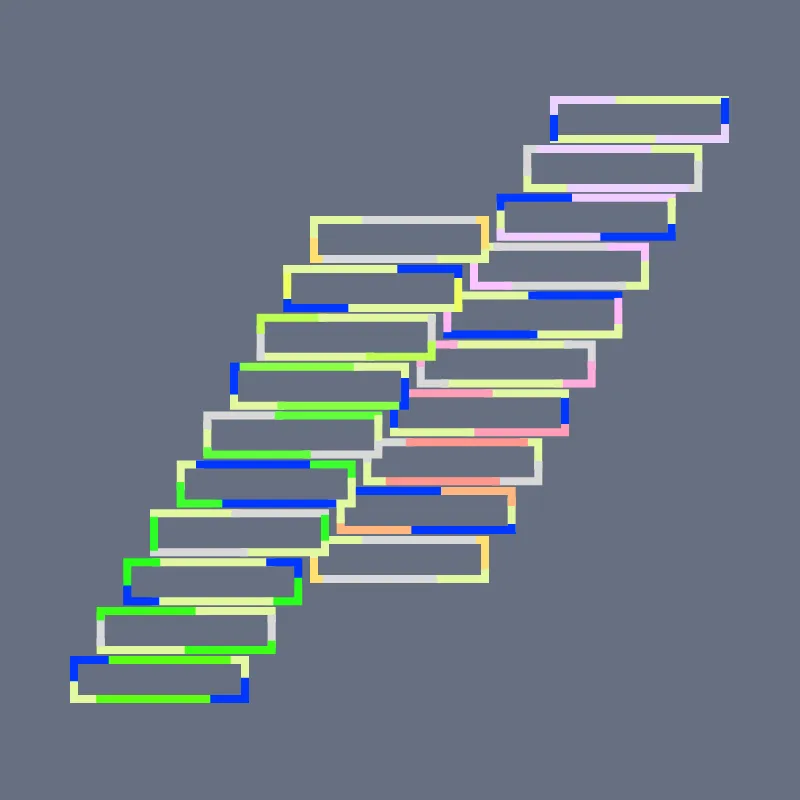

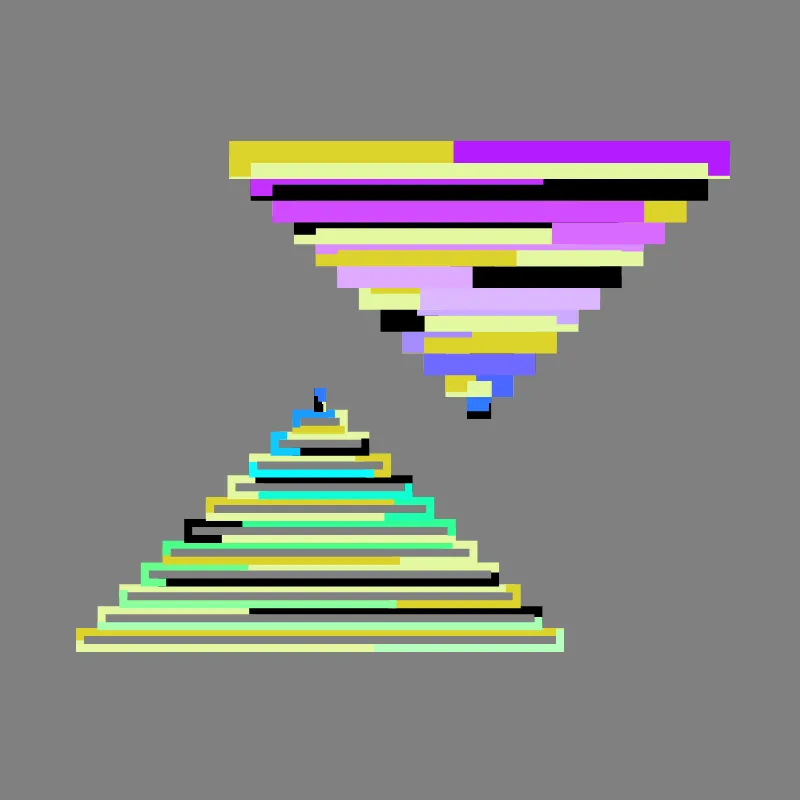

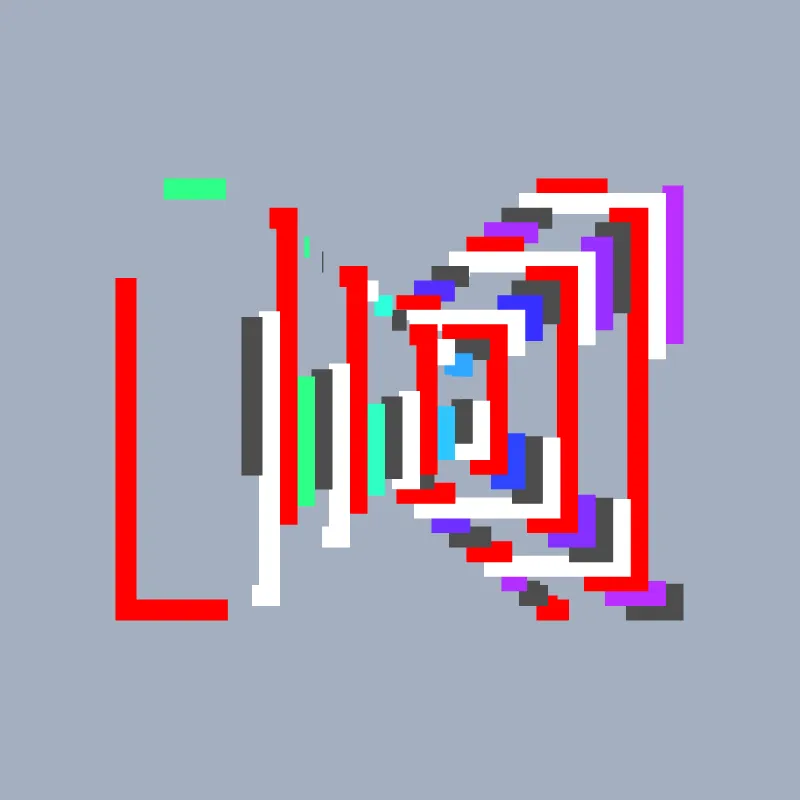

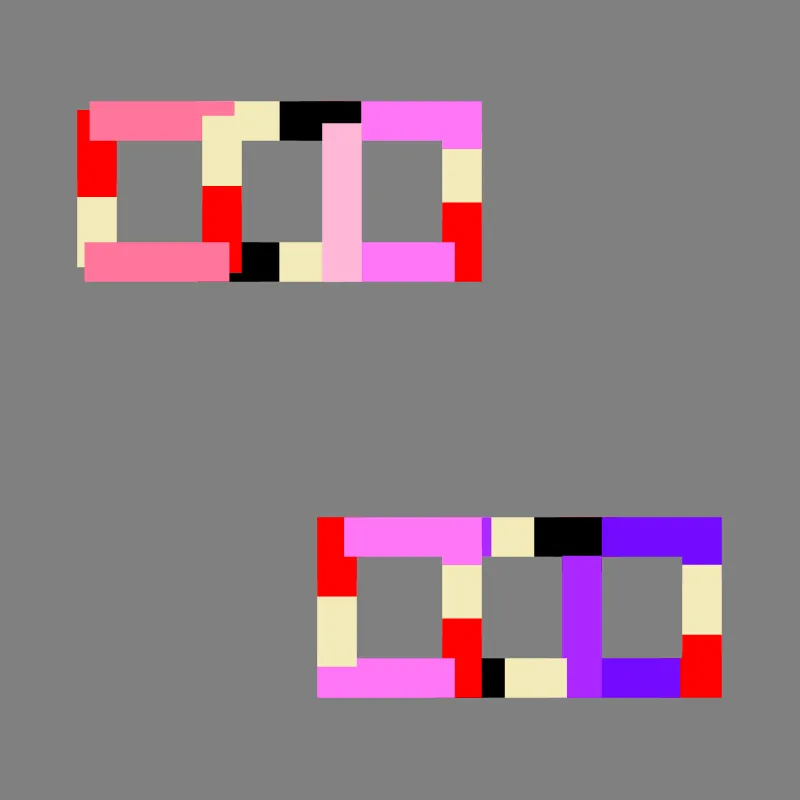

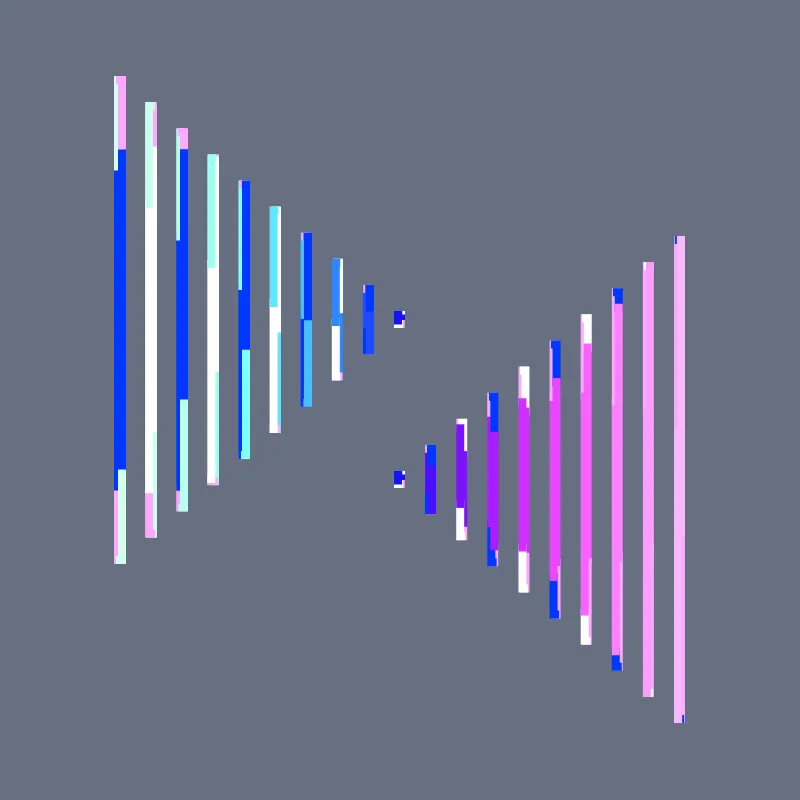

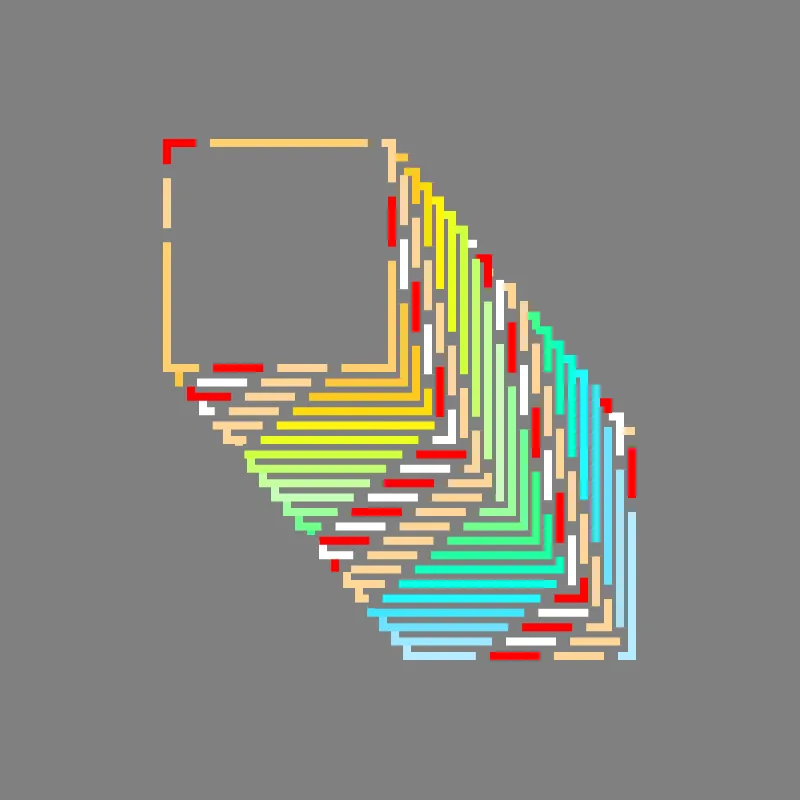

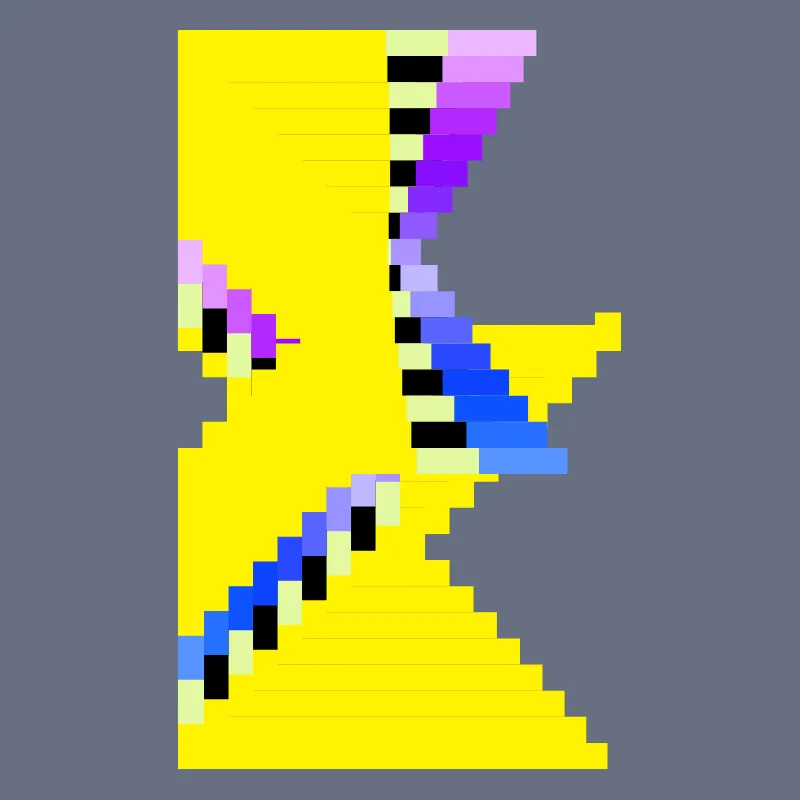

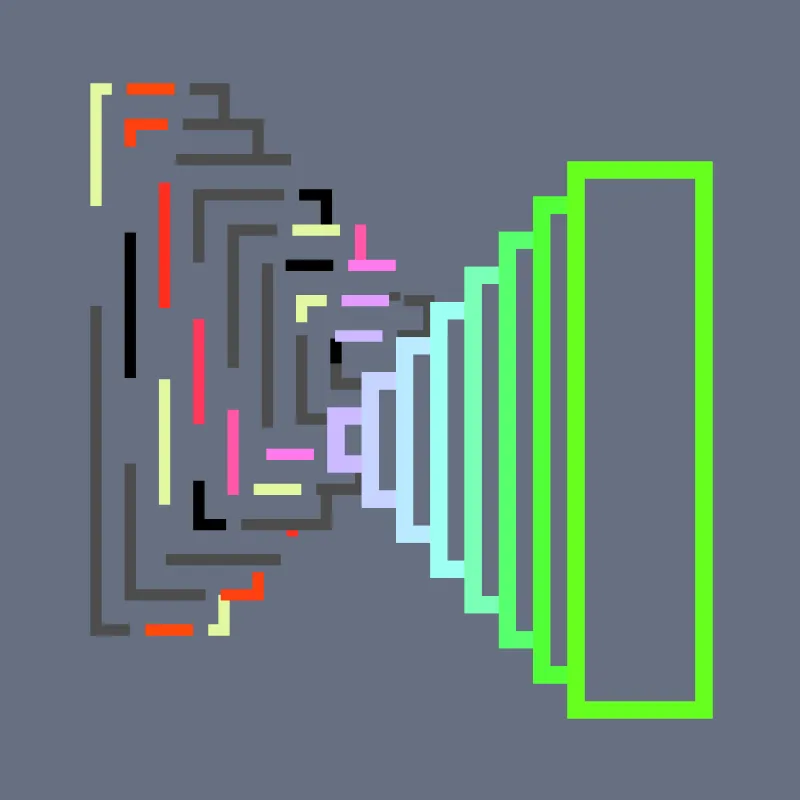

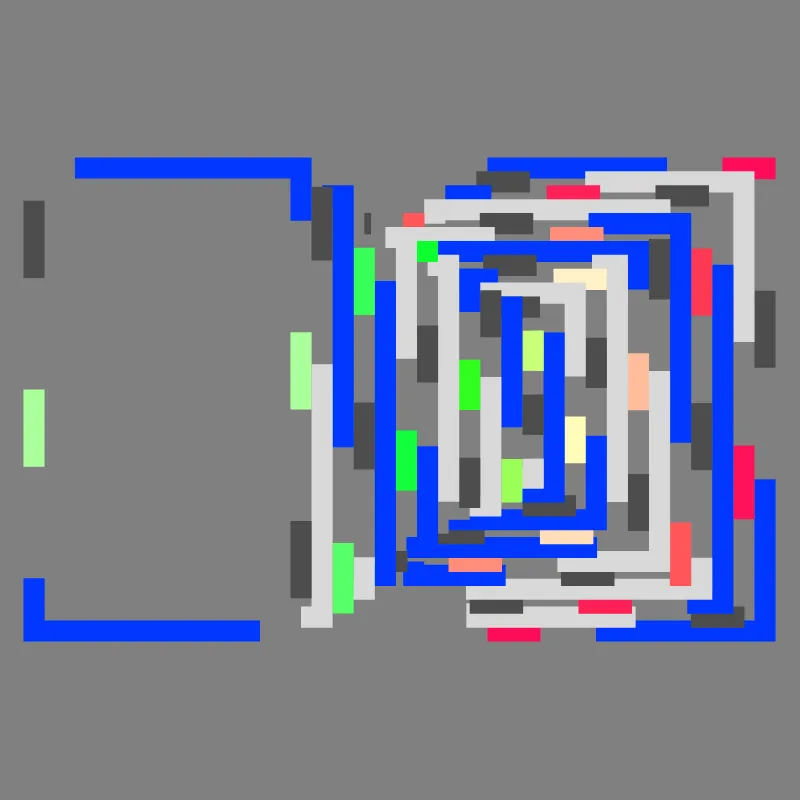

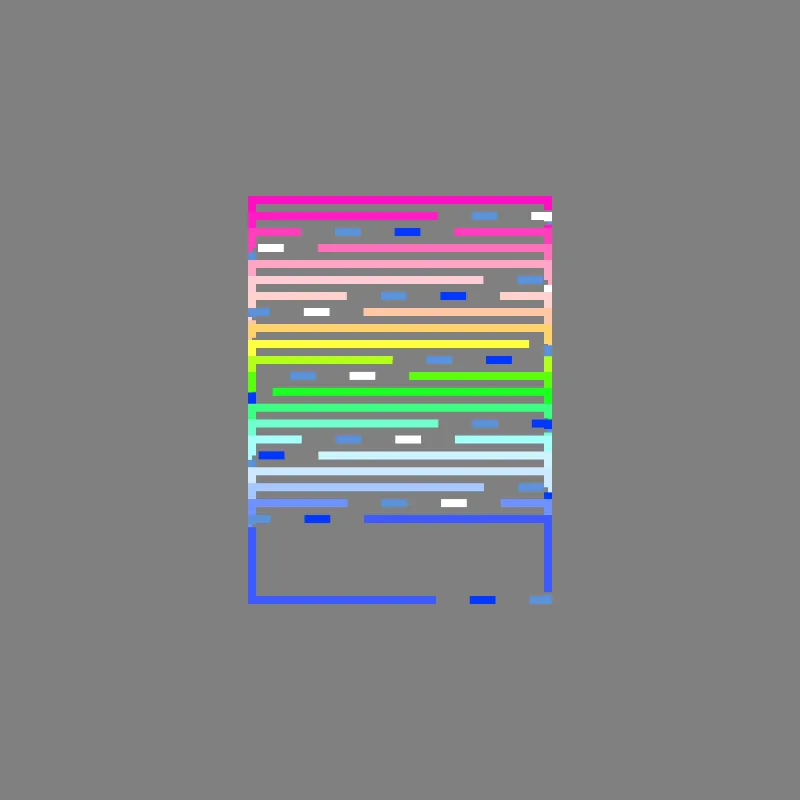

Two groups of shapes transform, merge and split randomly

2022Duet is a long-form generative artwork that was released in August 2022 on the fx(hash) platform.

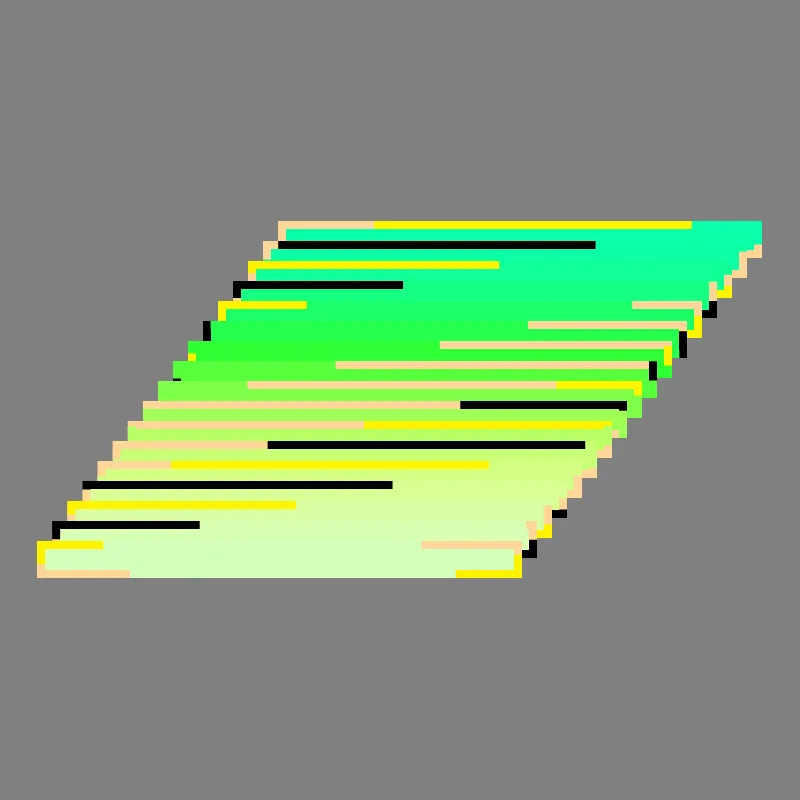

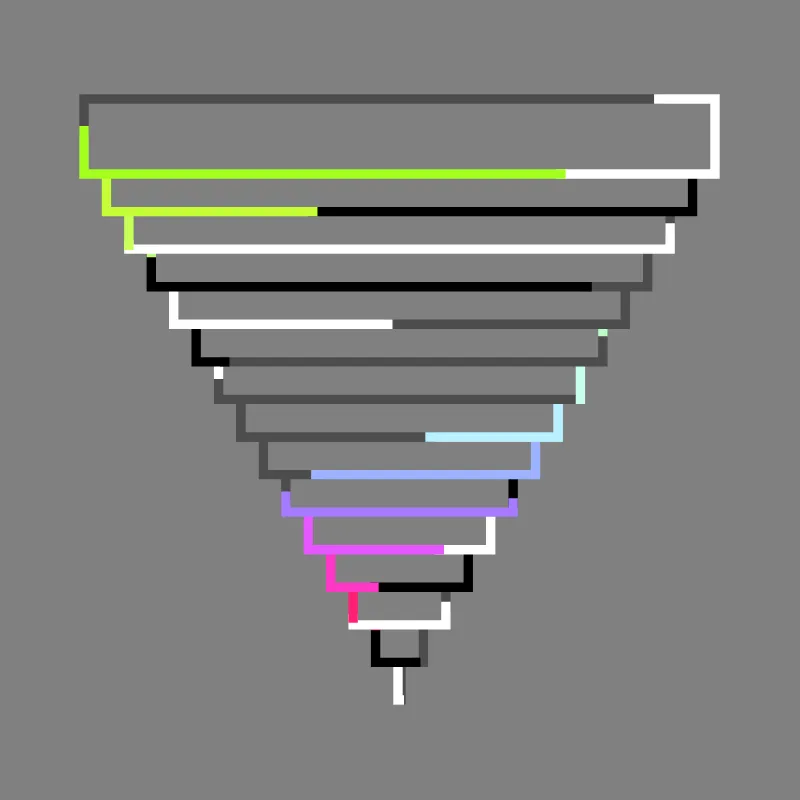

It explores generative + computational motion and creates an almost infinite sequence of visual compositions. Two groups of shapes transform, merge, and split randomly. What can be disorienting starts to make sense as every element is animated from one to the other. This transition animation is what connects random pieces and creates a relationship between them. Each element is mathematically interpolated, with its motion defined by an equation.

Although there are key moments, it is hard to summarize time-based work as a static image. As a constantly evolving generative motion piece, Duet invites viewers to form their impression by feeling the rhythm over time.

Introduction

Duet explores generative + computational motion and creates an almost infinite sequence of visual compositions. Two groups of shapes transform, merge, and split randomly. The properties of these visual elements are generated in real-time inside a viewer’s browser. They have nothing in common other than the rules initialized according to a transaction hash randomly assigned at the time of minting a token.

What can be disorienting starts to make sense as every element is animated from one to the other. This transition animation is what connects random pieces and creates a relationship between two unrelated numbers, forms, and compositions. Each element is mathematically interpolated. Interpolation is the process of finding in-between values. With what equation is used to interpolate determines the quality or characteristics of motion, and at what rate the values are sampled determines the smoothness of motion.

Although there are key moments, it is hard to summarize time-based work as a static image. As a constantly evolving generative motion piece, Duet invites viewers to form their impression by feeling the rhythm over time.

Background

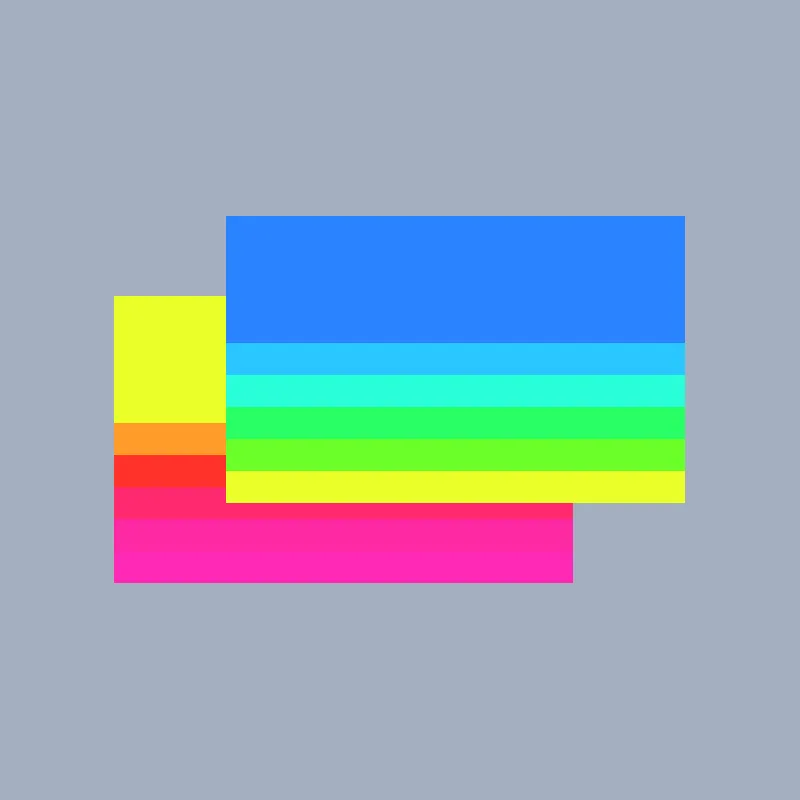

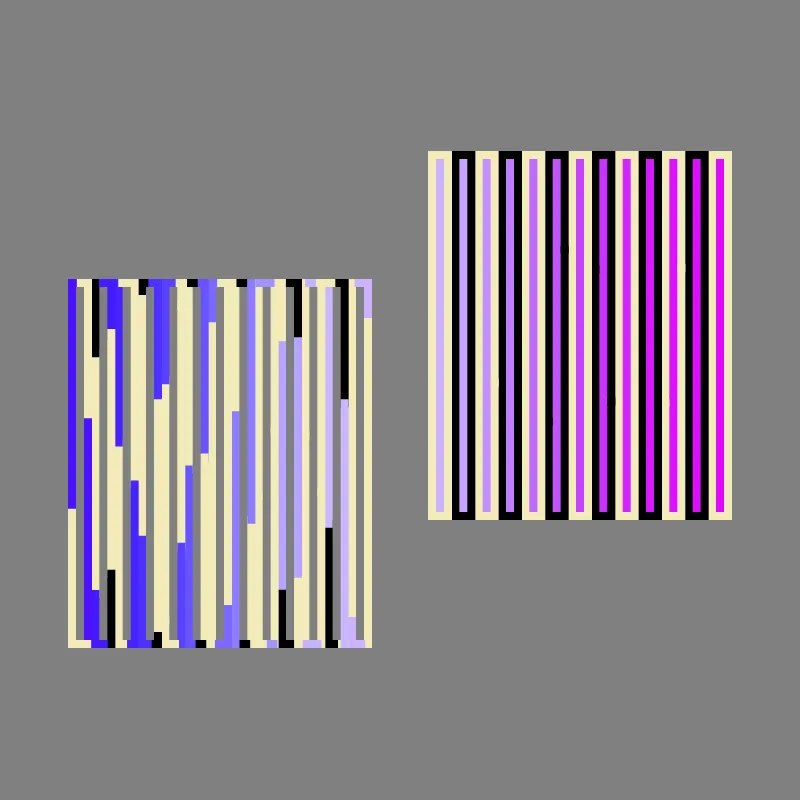

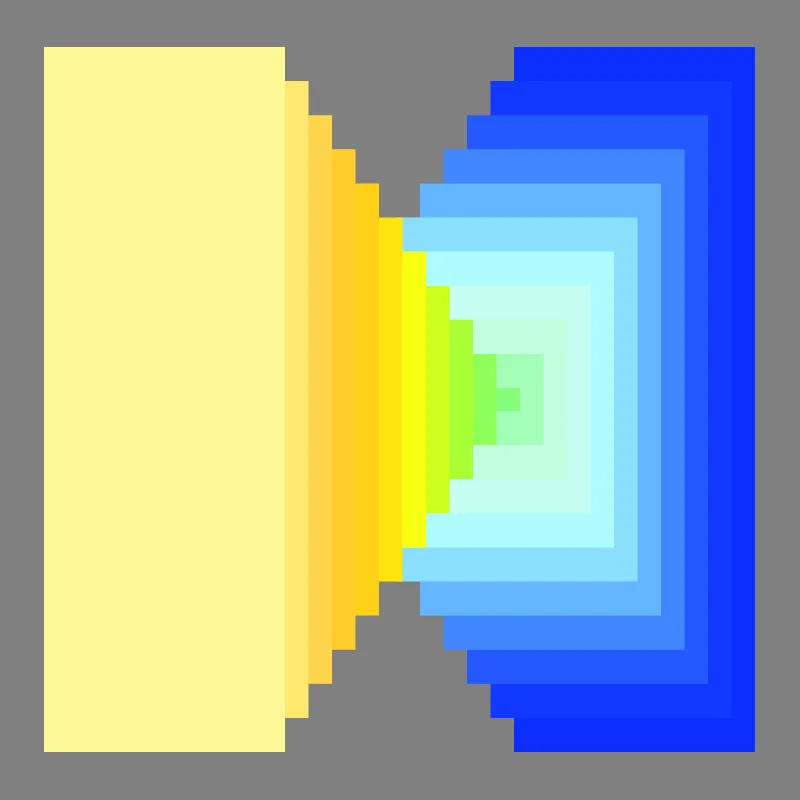

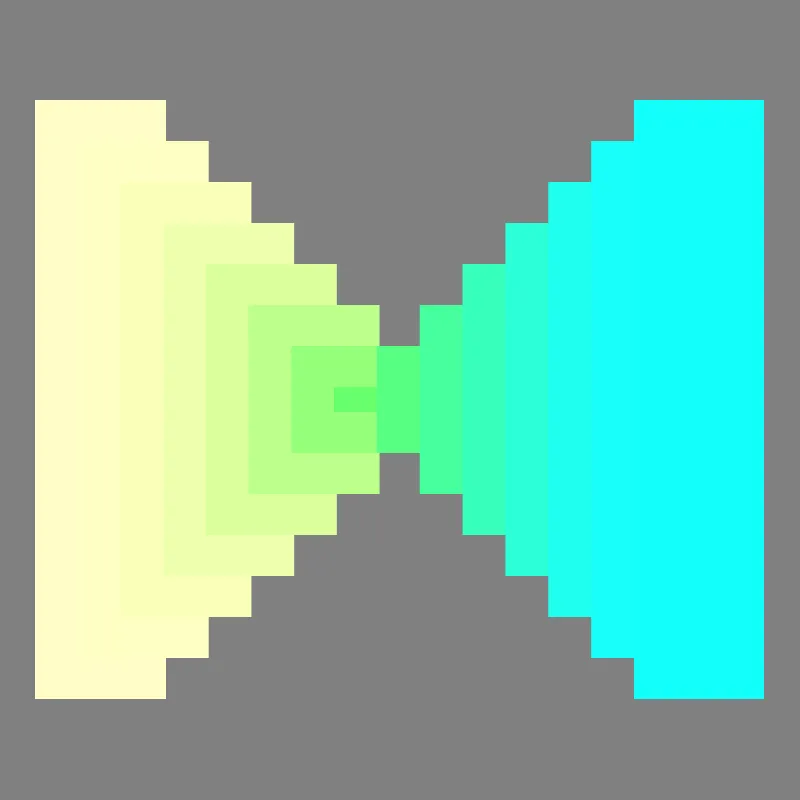

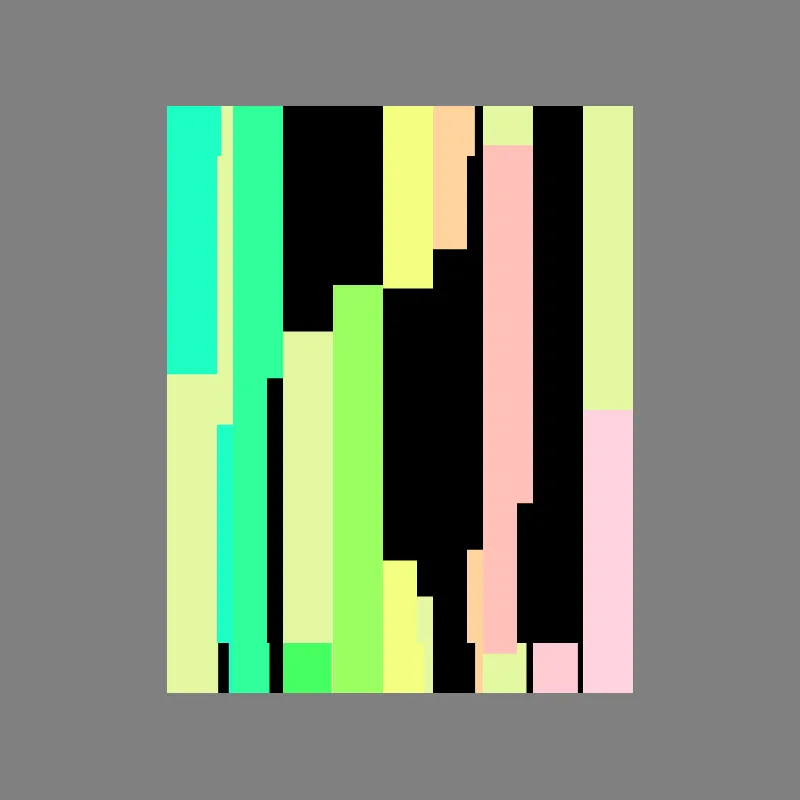

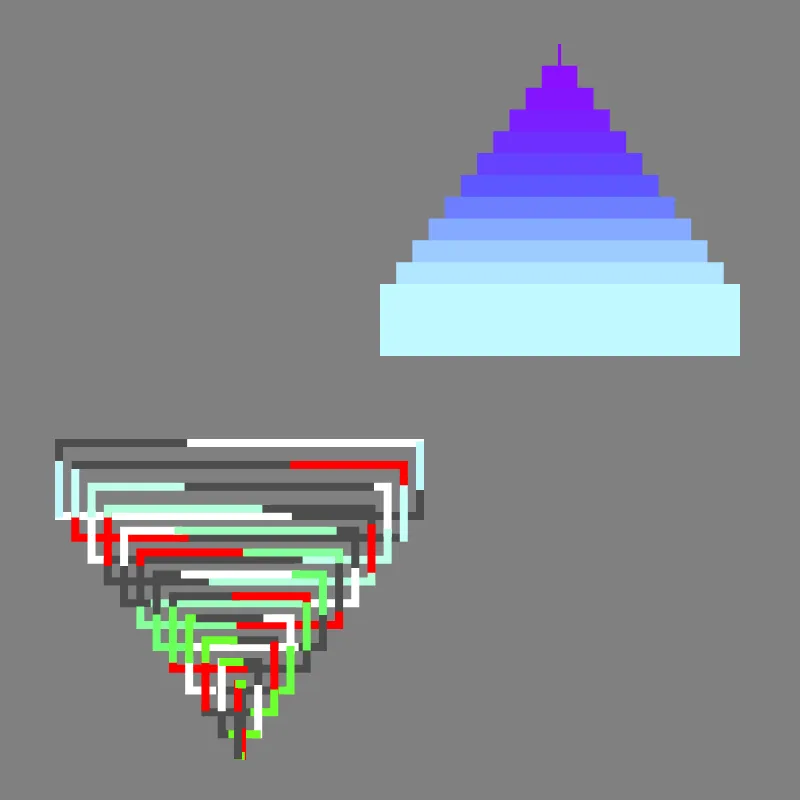

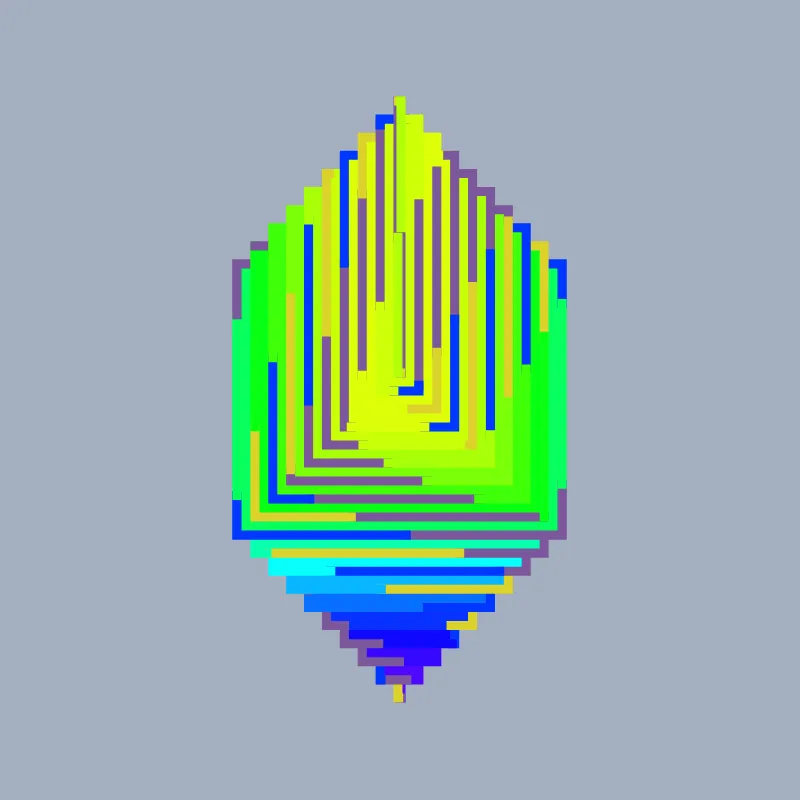

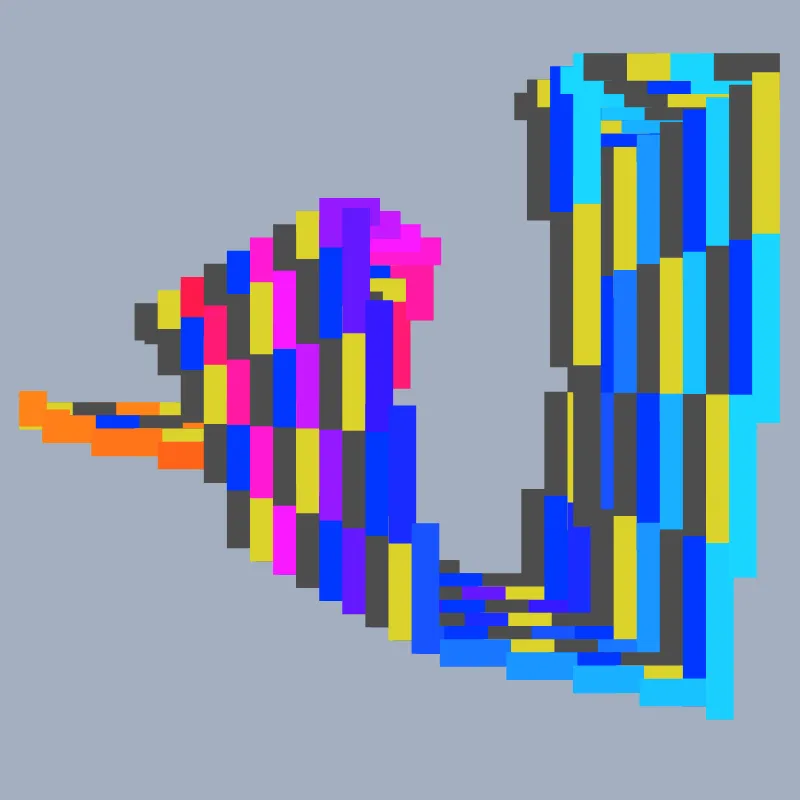

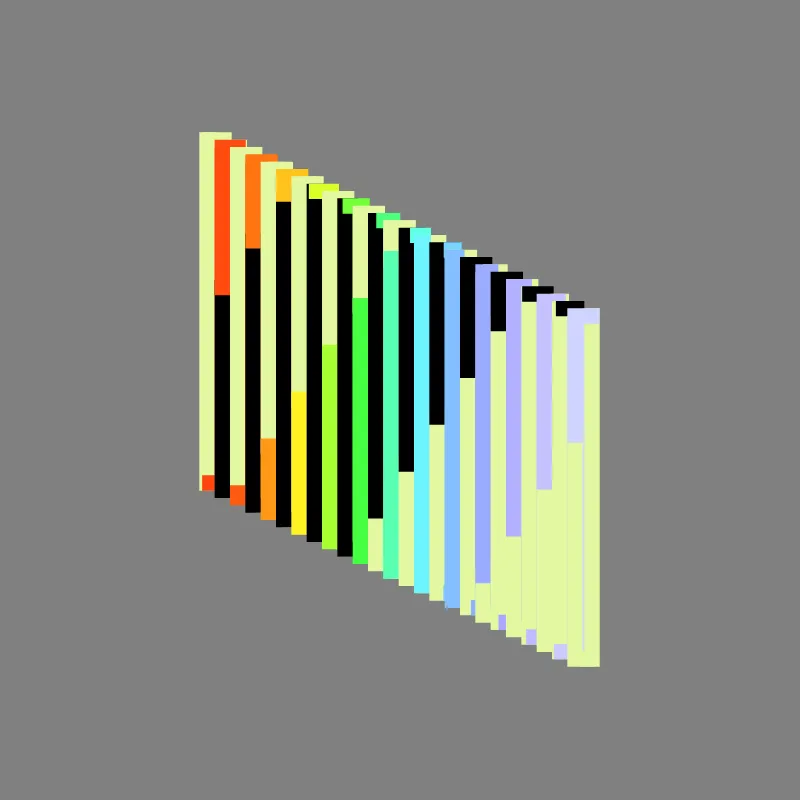

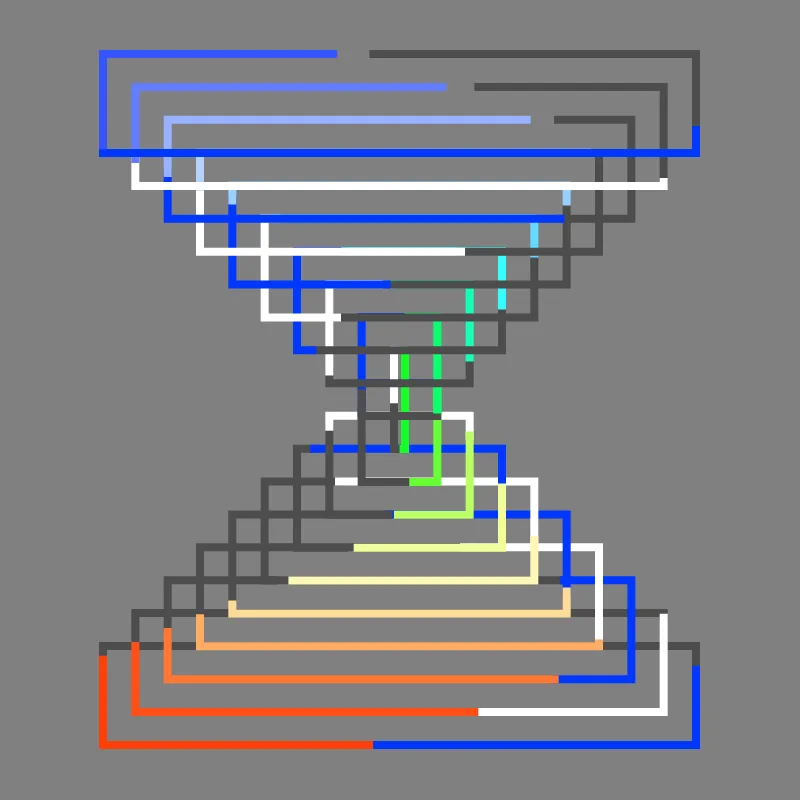

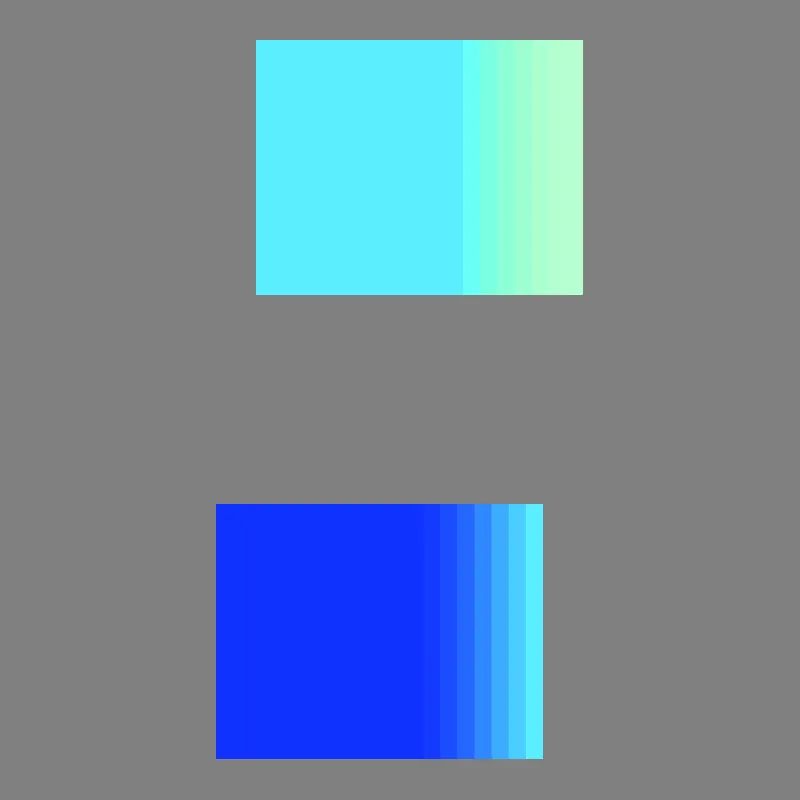

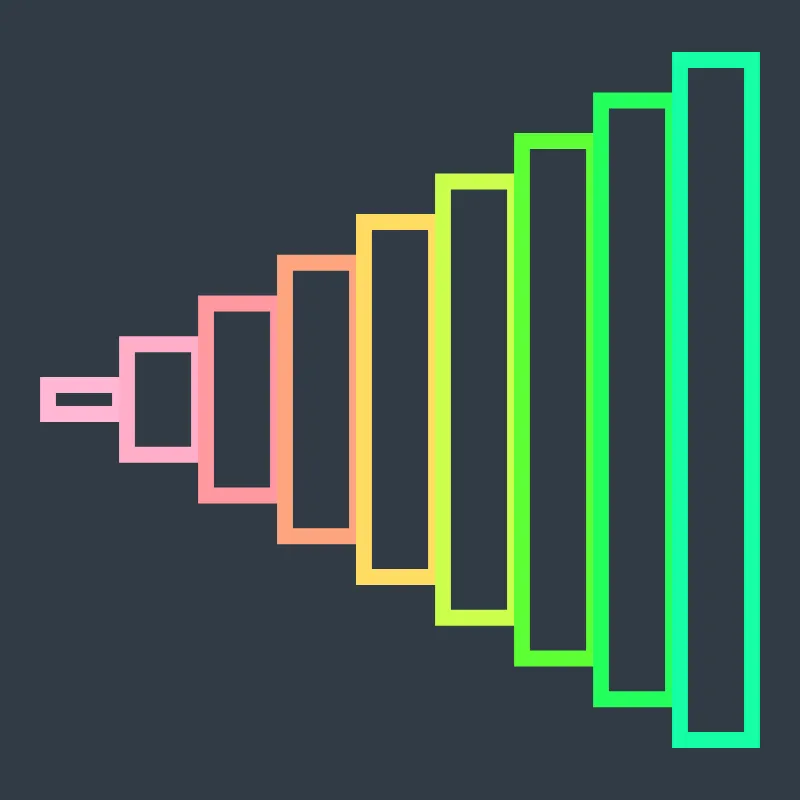

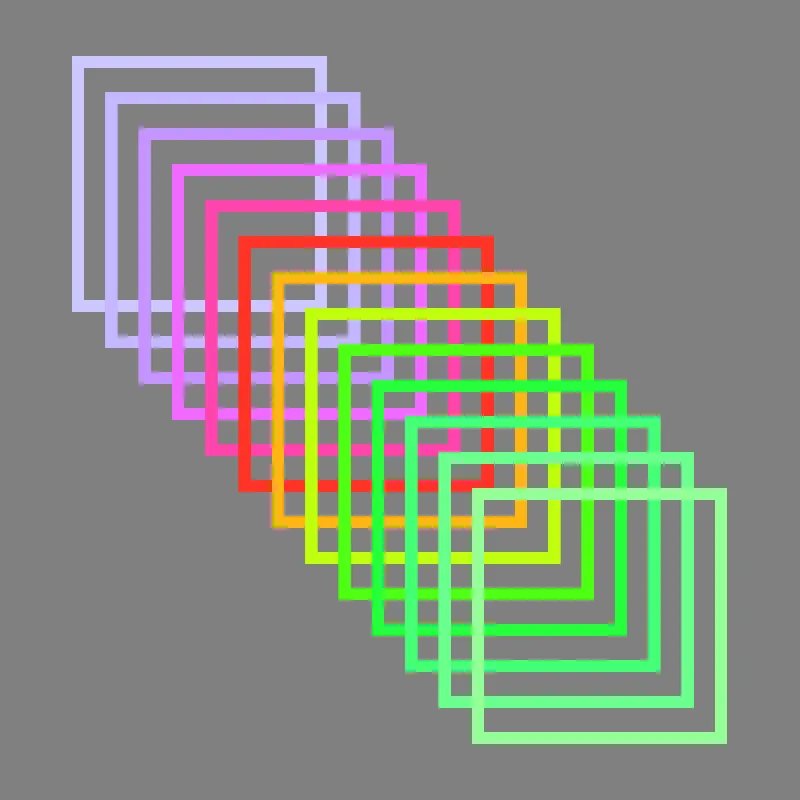

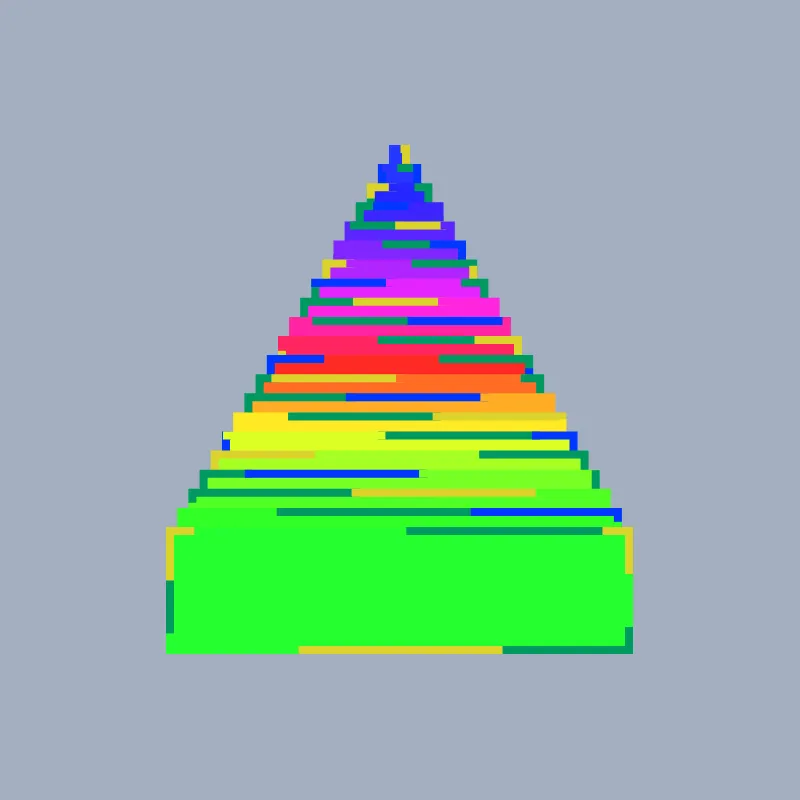

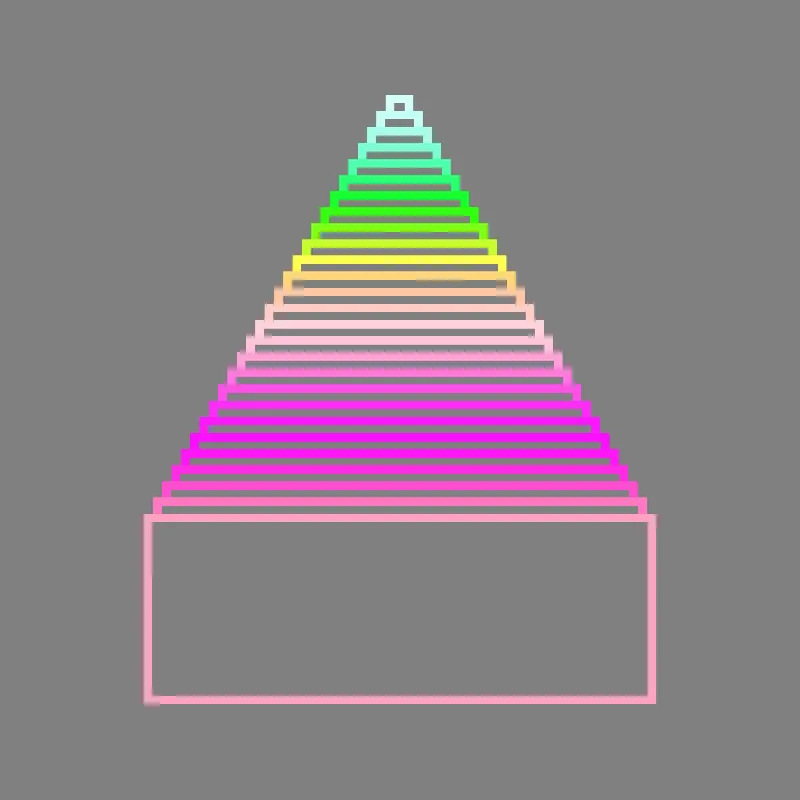

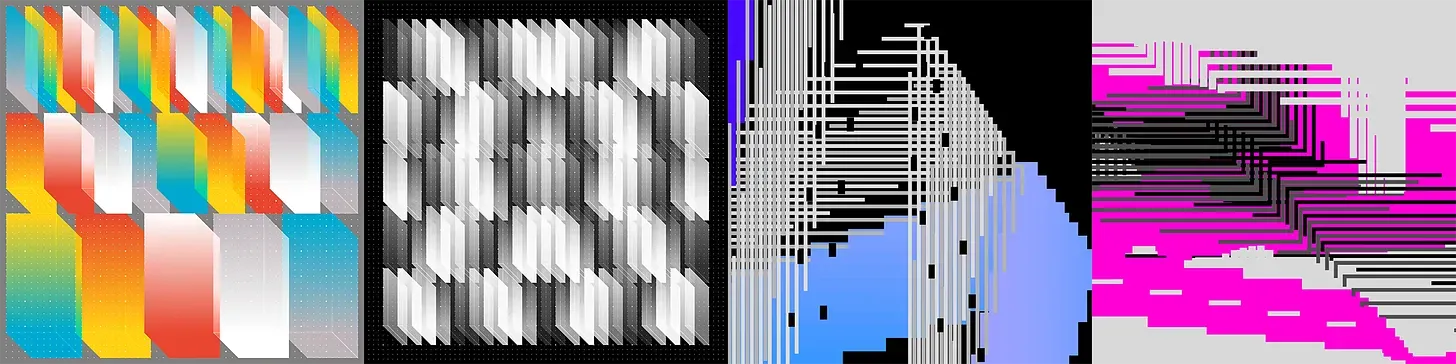

With recent projects, my main motive has been to explore and experiment with ways to represent time and motion with digital media mainly through computer programming. With the Structures series, I used my own software, Modular Design System One, to work with rigid grid structures. The colorful shaded rectangular blocks that look 3-dimensional are fixed in place, and essentially, act like big blown-up pixels. In this limited environment, only the colors change and create an illusion of motion. With my last long-form generative piece Time Intertwined, I explored two inter-connected or intertwined timelines to create an infinite number of fixed-length loops. Duet continues on that idea.

A few examples from Structures and Time Intertwined

Computational Motion

I am conscious of the medium and the tools I use to create work. I am interested in how and with what we create digital, time-based work. How much of what we create is enabled or limited by the tools we use? Why did I decide to work with computer code instead of paper or Adobe softwares? Is it because everyone was doing it? Is it because there are things that can only be done this way? We all know that a computer is a powerful tool that can do almost anything as long as we can provide the proper instructions. It is also a meta-tool that creates other tools. Early computer art pioneers had to either create their own tools or collaborate with those who could create for them. Compared to those old days, it has now become a lot more accessible and easier to work with the computer. But at the same time, it is also true that most of the time we use the same softwares and with a pre-defined finite set of menu items, for example, in After Effects for digital animation.

After Effects is great in its own right, but these days I am exploring alternative ways to create motion with my own software that I program. These tools may be simple and rudimentary compared to commercial softwares but they are flexible and allow me to do things that cannot be done otherwise. When I create software with code myself, I have direct access to all the underlying data and how they are combined to create motion, and through that process, I can make unexpected discoveries and develop my own visual expression. I feel there is still more we can do when we program digital motion ourselves. Below are a few ideas that I explored in Duet.

Timelines

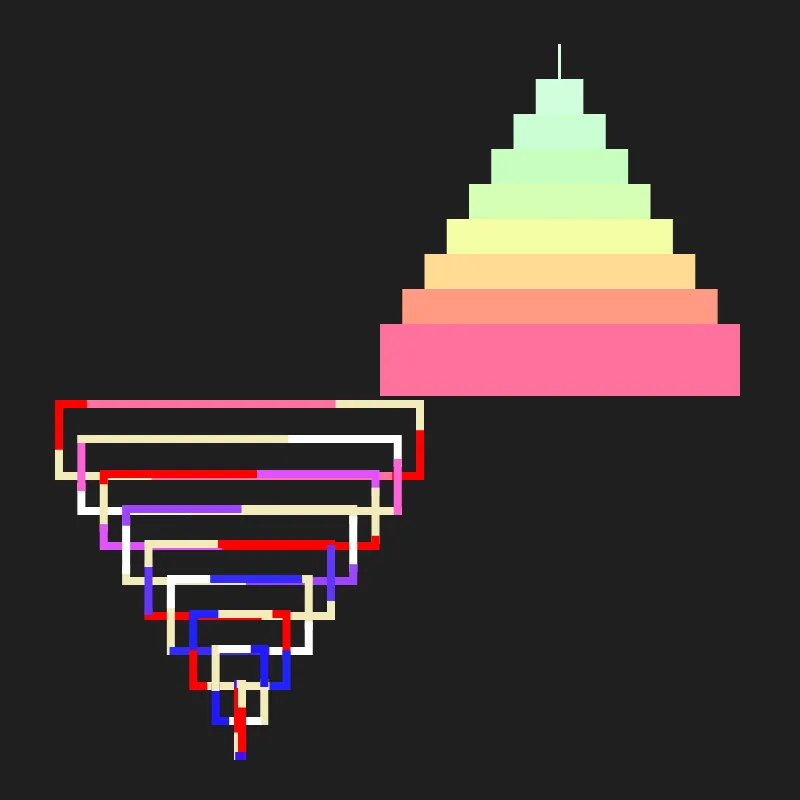

In my previous project, Time Intertwined, I explored two intertwined timelines. I have not yet found a good way to explain the idea but one way to think about it is the Earth rotating on its own axis as well as revolving around the Sun. Essentially, there are two connected timelines — one goes for a day and the other for a whole year. It isn’t just the duration of these timelines, but each has a different effect — changing day and night vs. seasons. In Time Intertwined, there are the structural timeline and the surficial timeline. The motion in each is linked just like in the example of the Earth and the Sun, but unlike the Earth-Sun relationship, it can be controlled independently from the other, which results in an almost infinite number of combinations, and creates a fixed-length loop or a cycle. In Duet, I expand this concept to have an infinite-length timeline.

Time, Not Frames

In a typical motion-based work, we need to define frame rate or frames per second so that the continuous time can be converted into a discreet set of images. In animation, it is the number of drawings per second. All the key timing and spacing rely on it. In a live-action film, it is how often time is sampled. We still need the frame rate in digital animation because that is how often the screen updates and refreshes the image. 24 or 30 fps has been good enough but with today’s technology, we are reaching the level that is almost indistinguishable from reality, or at least equal to or better than the analog counterpart. To me, there is something transcendental when I can no longer recognize the technology and get immersed in the work. Of course, it is still an illusion after all, but a very convincing one.

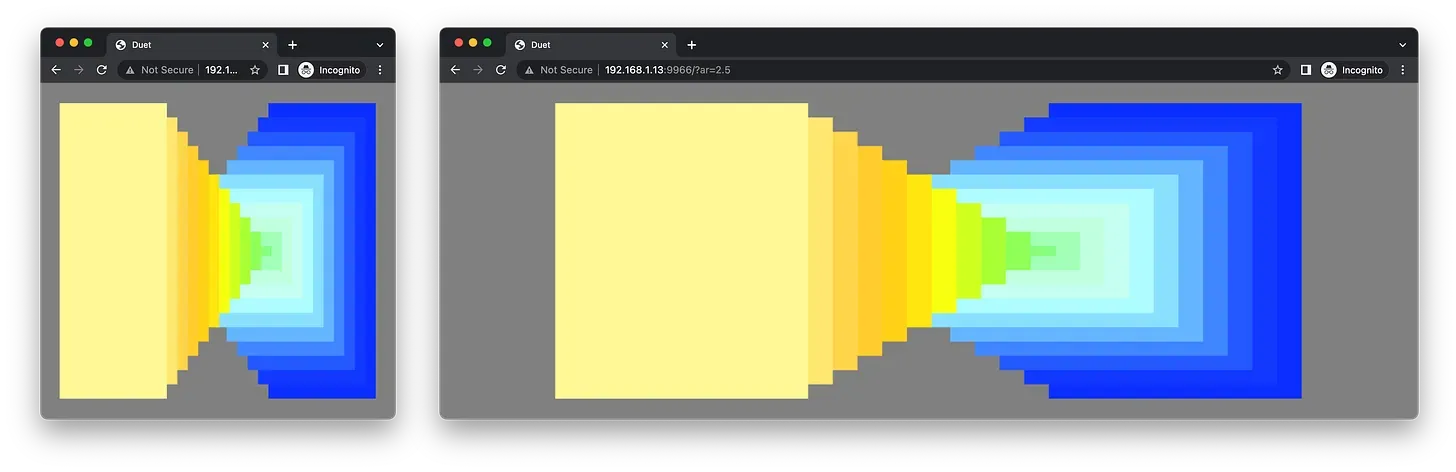

A typical computer screen supports up to 60 fps, but more recent monitors support 120fps or even higher. To adapt to different frame rates, I decided to use delta time that adapts to a screen’s refresh rate. This is nothing new to a game developer, by the way. I still use the concept of keyframes or key moments but every parameter of visual elements such as forms, motion paths, and colors are mathematically interpolated with an equation in real-time and the equation can spit out a value at any point in time no matter what frame rate is being used.

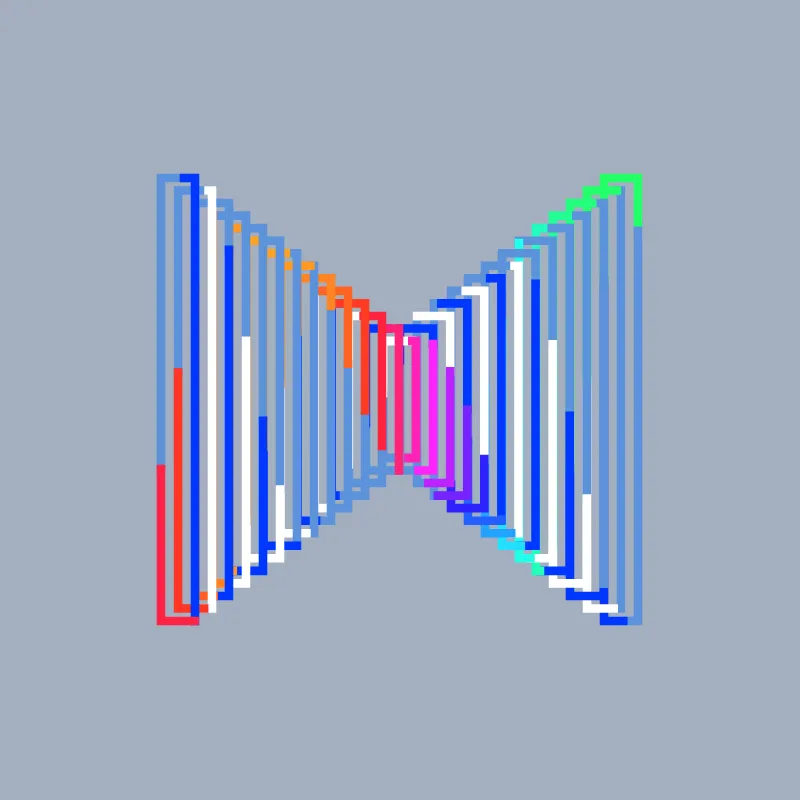

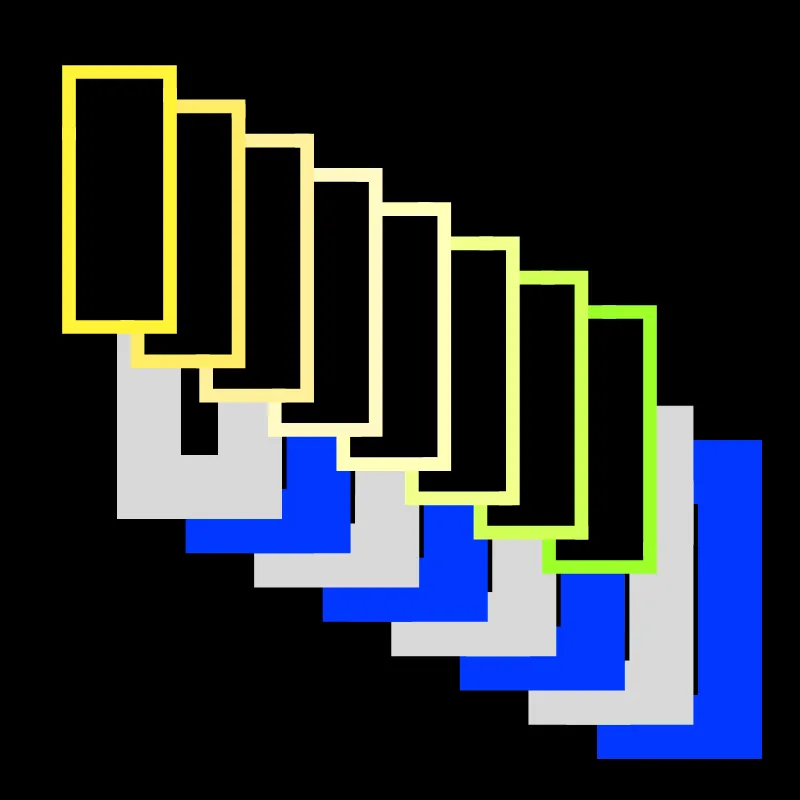

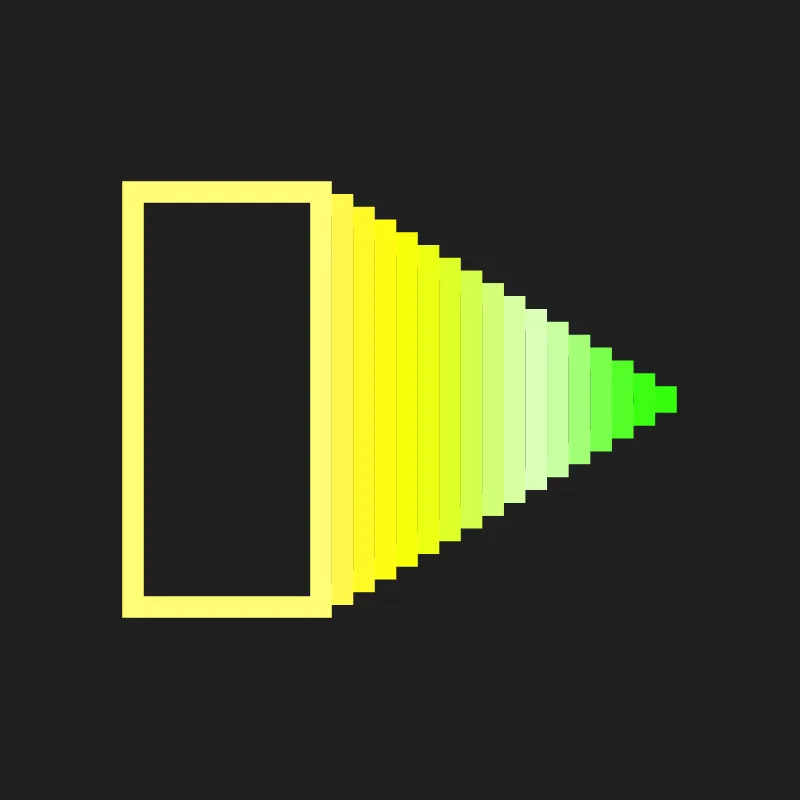

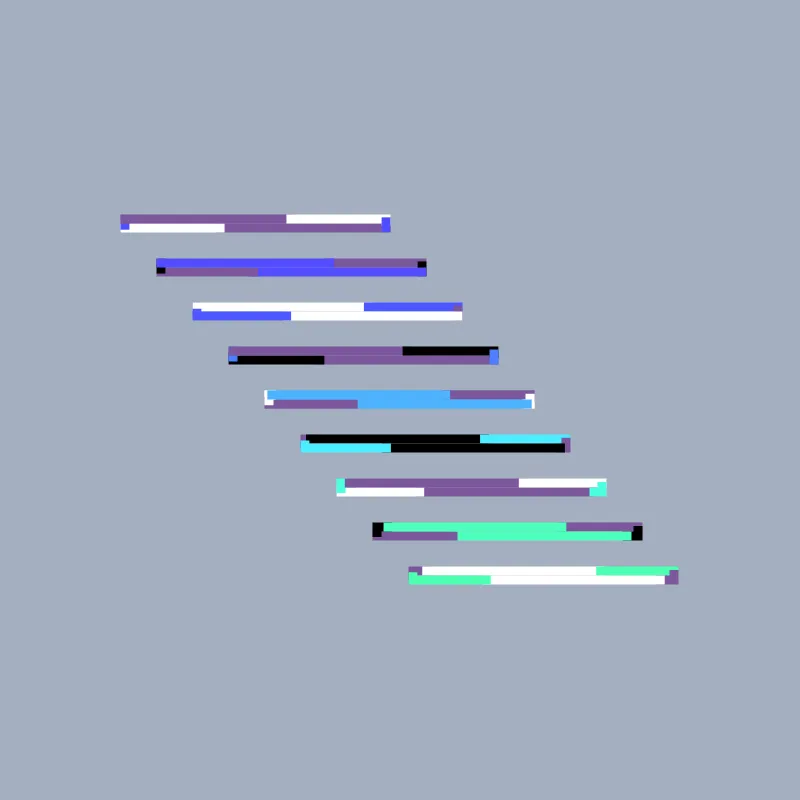

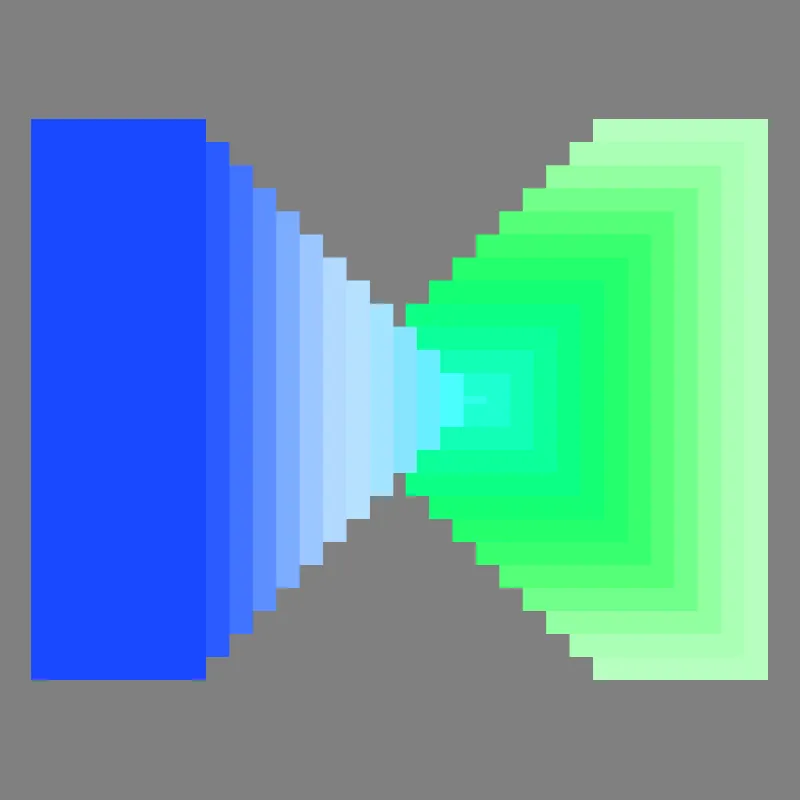

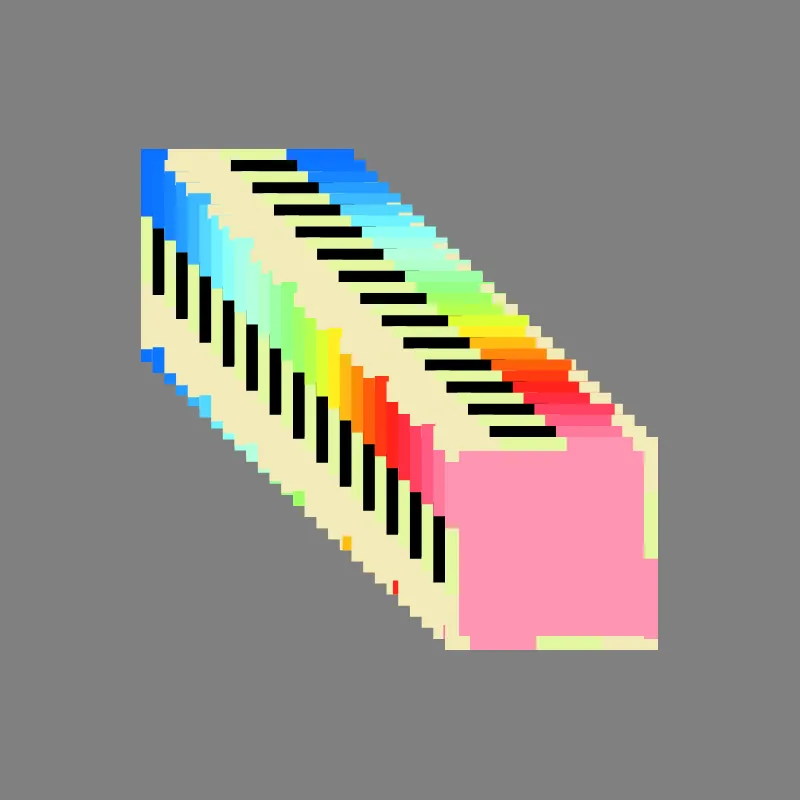

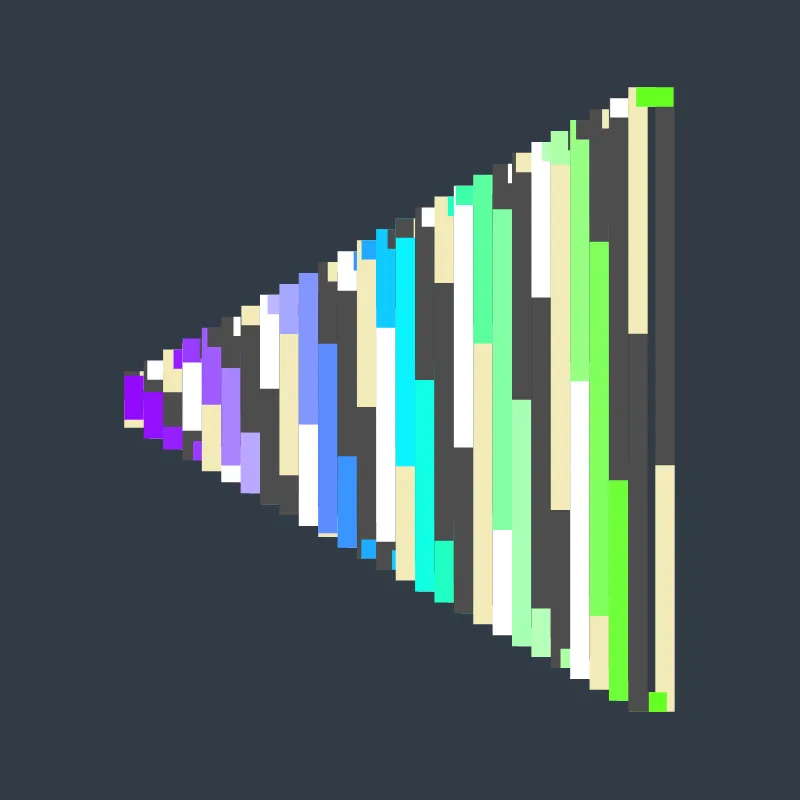

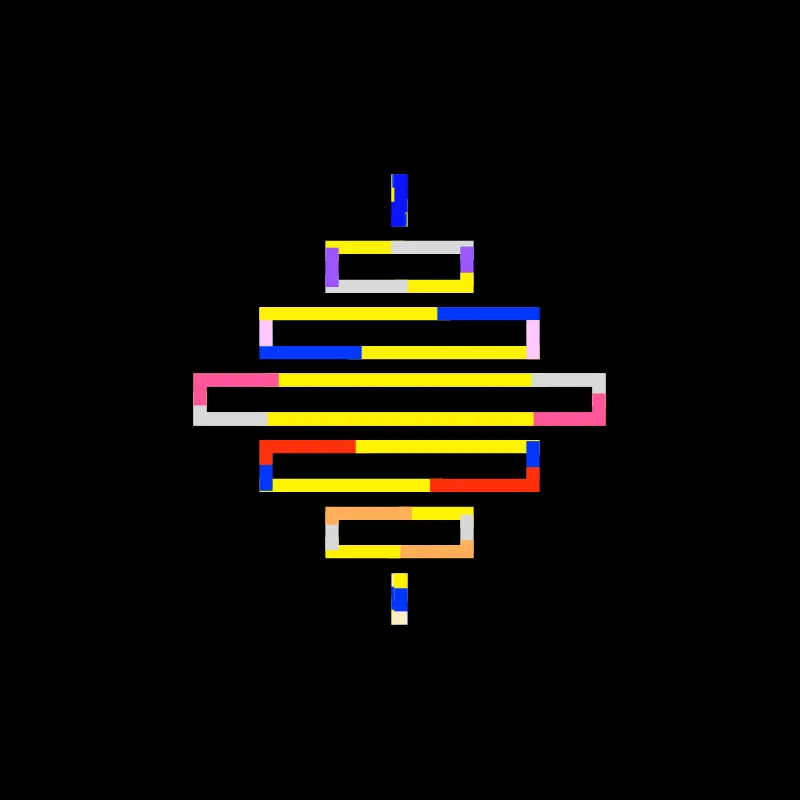

Duet #157 looping from 0 to 6.

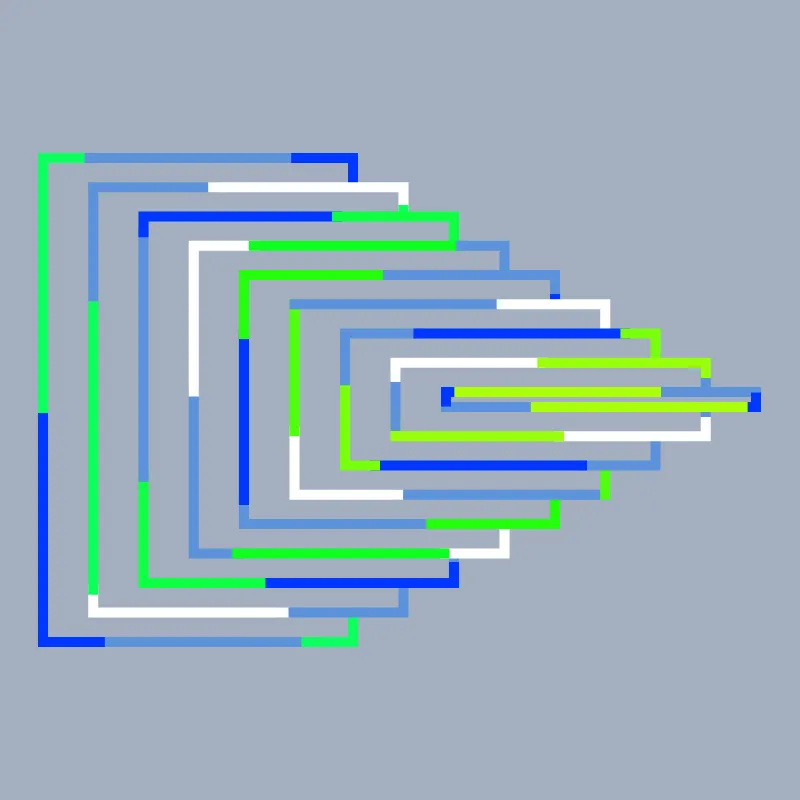

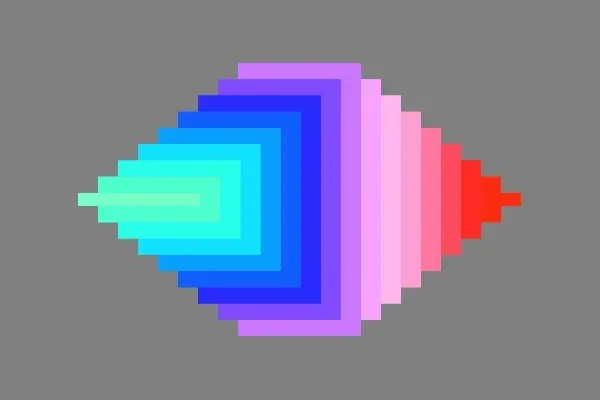

Duet #6 responding to different window sizes.

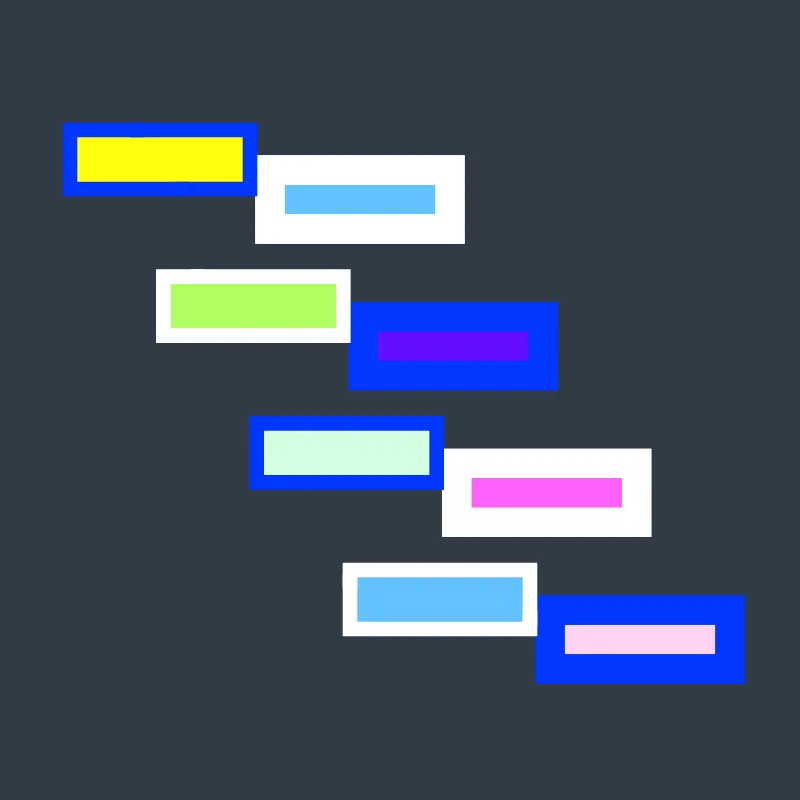

Responsiveness

In Duet, everything exists as code or computer instructions. The code gets executed only when the work is presented within a browser. As mentioned above, time is sampled in real-time instead of using the pre-defined frame rate. It also adapts to any screen resolution. This is different from pre-rendered digital videos where you have to adhere to any existing standards. Once the video is rendered, it can only have a fixed resolution, frame rate, and duration. Another point related to the real-time rendering is that the total file size of the Duet code is only 93 kilobytes. That is smaller than a typical single image file.

Visual Rhythm

Duet does not have any audio, but I took inspiration from music. I wanted to create a generative artwork about the visual rhythm that is not only seen but also felt over time. Rhythm comes from repetition. By default, Duet does not repeat the same animation twice. It looks like it is looping but it is not. If you want, however, it can go into the fixed-length loop mode, too, by pressing the “n” key. Every composition state is generated in real time according to a pre-determined random sequence of numbers. When you refresh the browser, it will play the same sequence of motion again from the beginning, but as long as you keep the window open, it will continue to generate a new composition. There is never a definitive ending to this piece. What is repeating is the rhythm that only comes alive when the work is played over time.

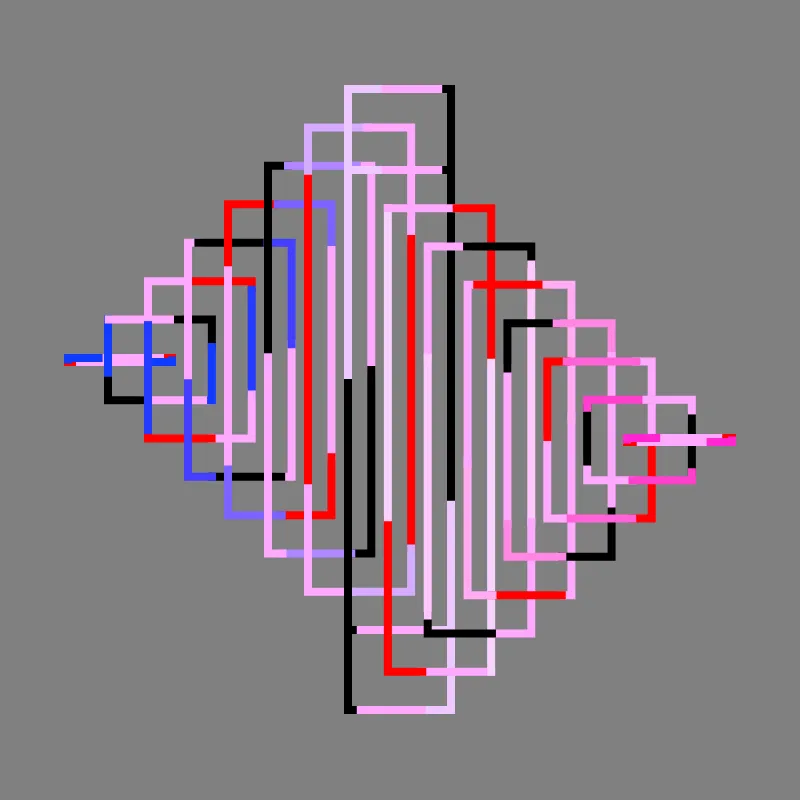

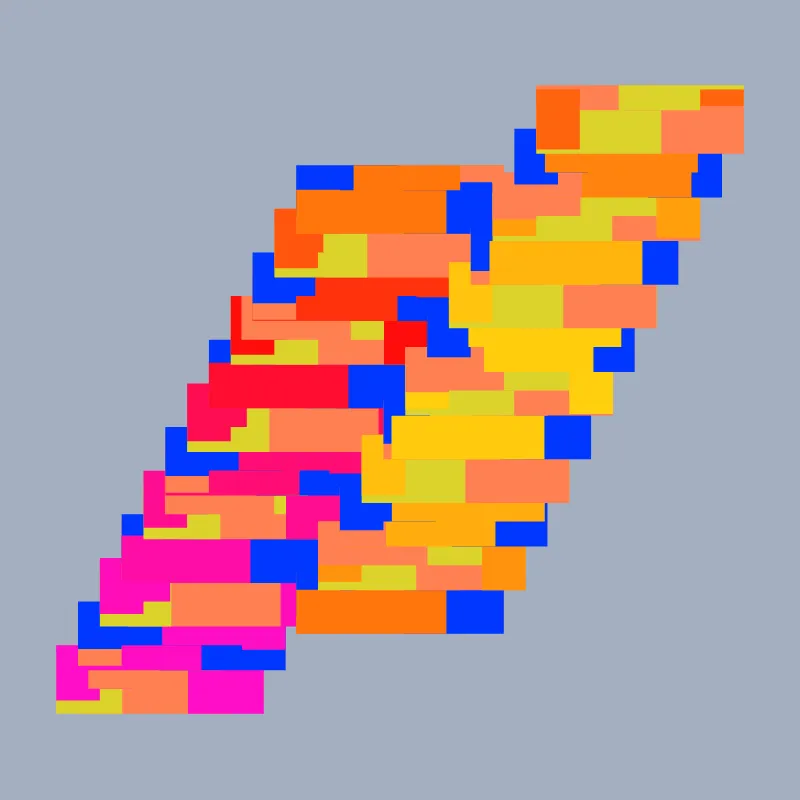

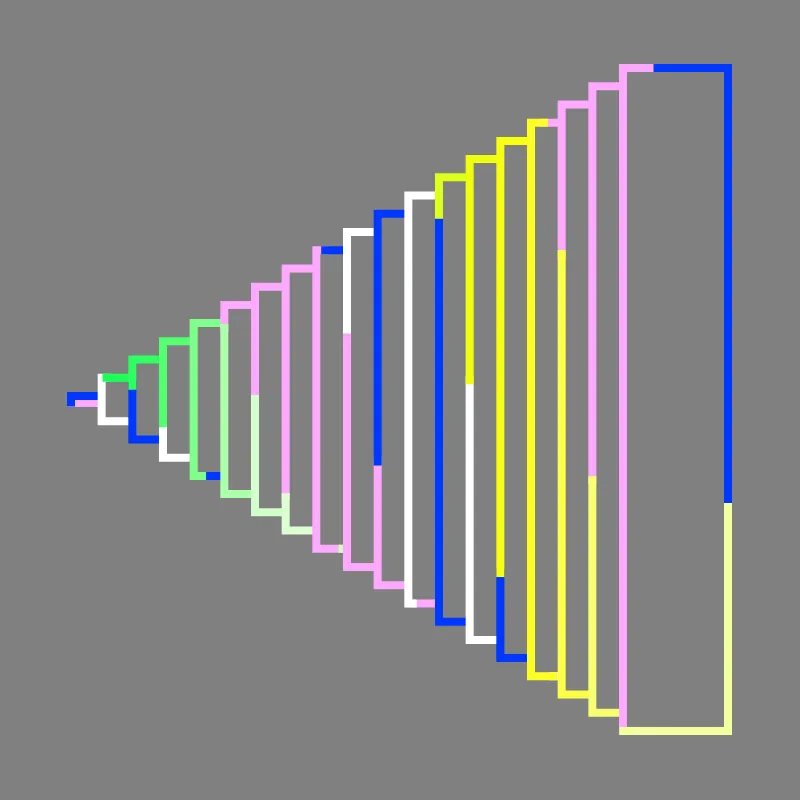

Generative Motion

As a generative motion piece, Duet endlessly generates a new composition within the boundary of a pre-defined set of parameters such as position, color, line thickness, etc. This set of parameters makes up the overall structure of the work and it is what I, the artist, decided to include, or not include, in the work. But the way these parameters are combined to create the final outcome is not in my control, and that is where the generative aspect comes into play. And because the motion sequence is never-ending, there is always something new to discover.

While working, I thought about how we experience an artwork, especially a time-based one. When we look at static artwork such as a painting, we still have to take time, move our eyes around, see from distance or up close, and take in different parts of the image at a time. In motion-based work, the perception of time is more obvious. And because the images keep changing, it’s hard to define or summarize a work as a single image. The essence of Duet is its motion and rhythm.

Among all the random composition variations, I found myself attached to a certain section and wanted the ability to only reproduce it without having to play all the way from the beginning. As a browser-based artwork, it was also important to have the ability to share interesting moments with others. Duet provides a way to navigate to any section by using the URL parameters, which will pre-run the generative functions up to that point.

Closing

Everything in Duet looks seamless and smooth thanks to the computational power of precise calculation. I have a personal desire to keep everything in perfect order and I have to fight not to go all the way because it can look too stable and not interesting anymore. There’s an irony here — I love to work with geometric forms and grids for their simplicity, orderliness, and proportional beauty, but at the same time, I’m deliberately trying to avoid being locked in them. The beauty is somewhere in-between. After all, what drives my work is motion which is about change.

I also have to keep reminding myself that nothing in life is perfect. In fact, what I found while working on Duet was that it was not the case at all. The seemingly perfect look is the ideal that I was pursuing, but in reality, I had to make a lot of adjustments to make it look seamless. Technology is never perfect, and even though I am directly manipulating computer code without any intermediary interface, I still have to rely on a lot of infrastructures to make it work. For example, I had to consider how browsers behaved differently. There is never a perfect solution. Instead, I have to embrace the fact that not everything is in my control just like I do not know what random composition Duet will generate next.

Duet received an overwhelming response from collectors and minted out quickly except for the six reserved tokens for future use myself. Currently, the 250 minted iterations are owned by 157 collector wallets on the Tezos blockchain. I am motivated by all the support I got. I will continue to use this newly developing decentralized space to share and release my future digital artworks.

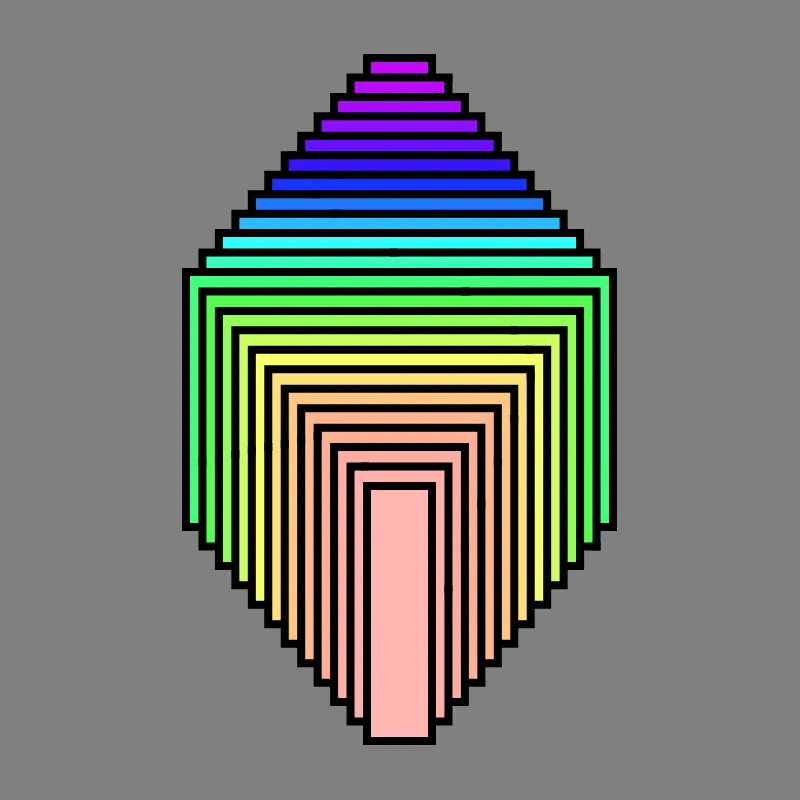

Click each image below to see live version of the minted tokens.

Selected Exhibitions

- Bideotikan Digital Art Festival, Bilbao, Spain, 2024

Check the project page for instructions on keyboard interactions and URL parameter settings.